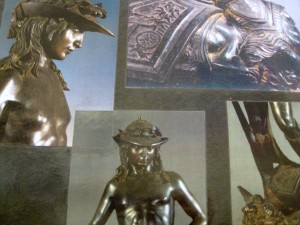

1. Bust of Lorenzo de Medici (Lorenzo the Magnificent)

2. David (marble) by Donatello

3. David (bronze) by Donatello

4. Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci

5. Mona Moi (“Miss Piggy” version of Mona Lisa)

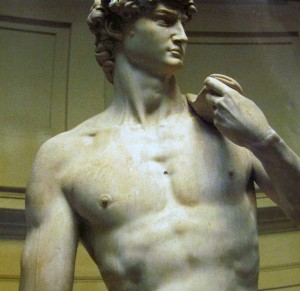

7. David (marble) by Michelangelo

8. School of Athens (fresco) by Raphael

9. St. George and the Dragon by Raphael

Packet Extras:

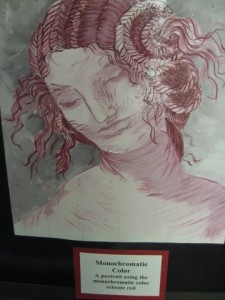

“Head of a Woman”by Michelangelo. Drawing in red chalk.

“Leonardo da Vinci sketch of a woman”

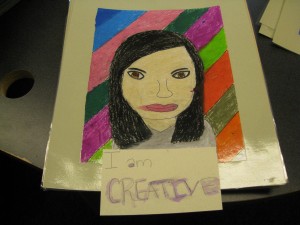

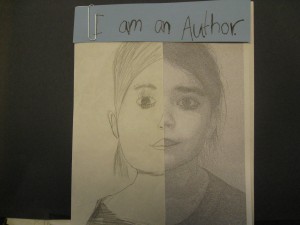

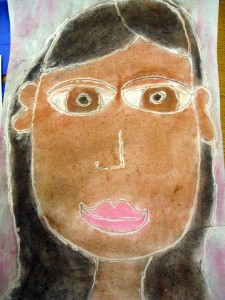

Sample Projects:

Classical Art: the ancient art of the Greeks and later the Romans, who admired and tried to duplicate the styles of Greek art

“Renaissance” means rebirth in French. The artists of the 1400’s and 1500’s brought back ideas and art that had been forgotten since the ancient days of Greece and Rome. This ancient time is now referred to as the Classical Age. Ancient Greek and Roman classical philosophy was being read and collected by Renaissance scholars of the 1400’s and 1500’s, just as Classical Art from all over Italy. The ideas and discoveries of these ancients were finally being “reborn” or rediscovered and improved upon. Art, architecture, science, education, and exploration suddenly became new and exiting!

The art and artists of Florence, Italy were a major influence on the art of the Renaissance. Four of the most famous and talented artists of the Renaissance—Donatello, Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael—were born in or near Florence and major chapters of their artistic careers took place there. The Medici (MED ee chee) family, especially Lorenzo, used much of their influence and money to support the new arts and learning in Florence and their influence had a strong affect on the art of other Renaissance Italian and European cities.

The “Ninja Turtles” cartoon characters were named after these four major Renaissance artists. As the story goes, after four pet turtles were thrown down a sewer, then accidentally covered in mysterious radioactive “goo”, they were “reborn” into half human, half turtle superheroes. These artists’ names will probably be familiar to many kids because of the Ninja cartoon characters. Take advantage of this as you teach kids a few facts about the “real” people behind those names and discuss aspects of their art.

This packet features mostly sculpture. If you would like to focus more on fresco, refer to information from Rotation #2, Packet 7. Balance and Symmetry (The Last Supper) and Packet 13. Fresco Art. Art of The Last Supper and views of the Sistine Chapel are easy to find on the internet or in books.

Make sure ALL 8 pictures are returned to the Packet Carrier after your Presentation is finished!

A Brief History Lesson on the Renaissance in Florence, Italy

(Historical information is to clarify and define this historical era FOR ART DISCOVERY VOLUNTEERS! Information is not intended as intense study for kids. Reading the historical background information should help Volunteers feel better prepared as they present this packet.)

The word Renaissance was never used to describe the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (1400’s – 1600) until 1860. This was when the Swiss historian of art and culture, Jacob Burkhardt, wrote a book titled The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. Burkhardt was the first to demonstrate the research of a period in history in its entirety—including not just the paintings, sculpture and architecture, but the social institutions of the people’s daily lives as well. He felt that those two centuries made up an important era in the history of the Western civilization.

Renaissance, which means “rebirth” in the French language, refers to a time when Italians had discovered the great literature, written in Greek and Latin, by ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, mathematicians and scientists. Beautiful ancient Greek and Roman sculpture and architecture were also being admired, respected, collected and copied. The ideas expressed by this ancient literature and art had been forgotten throughout the middle Ages. Scholarly Italians began to study these ancient antiquities and the ideas they communicated seemed new and inspiring. Historians call the period in history when ancient Greece and Rome were major world powers, the Classical Age. These newly rediscovered Classical Age ideas began a “rebirth”, or a renaissance, which inspired new knowledge and thought for fifteenth and sixteenth century Europeans.

The Greek and Roman cultures had existed in Europe long before the 15th and 16th centuries. The Classical Age began with the earliest recorded Greek poetry of Homer, roughly around the 8th century BC, and ended before the fall of Rome and its empire, in AD 410. The Italians responded to the collapse of the Roman government differently than other Europeans.

Thanks to a strong Roman military government, Europeans had previously enjoyed a relatively peaceful existence. As the Roman Empire weakened and eventually fell, war became a constant problem throughout Europe. The Feudal system evolved throughout most of Europe to give communities safety and protection. Common folk exchanged their land, livestock, and freedoms for the right to run away into the local Feudal Lord’s castle whenever raiders attacked. In exchange for this protection of their families, the men were required to serve their noble Lord as his soldiers.

Instead of exchanging their freedoms and properties for feudal protection, Italians formed themselves into small, self-ruling and independent city-states. The Democratic ideals of the Roman Empire were another legacy that guided the Italians as they established their new governments. Italians lived in the most well developed cities of Europe. The Roman Empire had been an urban empire and believed that civilization needed cities to prosper. Long after Roman government left Italy, the well-planned and fortified cities remained. Italian states centered on the important city of each region. These cities with secure and protective walls gave far better protection than a Lord’s castle, without the loss of personal freedom and property. Because of this, feudalism did not take place in Italy.

During the Late Middle Ages, the Italians were also more active in trade than the rest of Europe. City-states like Venice, Pisa and Genoa sent out fleets of merchant ships to the more sophisticated Islamic and Middle Eastern civilizations. These areas of the world traded spices, medicines and luxurious cloth to the Italians. At the same time, new ideas in art, technology, science and philosophy flowed back into Italy through these trading areas. A new age of enlightenment, learning, and discovery was beginning to develop in Italy.

Because of wars between various European monarchies throughout the Middle Ages, European kings needed money for professional soldiers and weapons. Prosperous trade gave Italians the money to lend to their northern neighbors at high interest rates. While the rest of Europe was going into debt fighting wars during the Middle Ages, Italy was becoming a strong economic European world power.

At the beginning of the fifteenth century, Italy was a powerfully secure country compared to the rest of the world. At this time, one family with great skill and intelligence managed to head the city-state of Florence, Italy, despite resistance from a few other influential families. This family was the powerful Medici (MED ee chee) family. Their strength came from banking.

In Renaissance Italy, making money and getting rich the way the world does today was considered sinful—the Catholic Church even banned banks from charging interest on loans! This did not stop anyone from trying to get rich though. Those who became rich using the new tools of commerce and loans usually felt an obligation to God to give something back to society in exchange for the blessings of their wealth (and as an extra “bargaining chip” with God for going against the mandates of the church). A popular way for rich bankers and merchants to give back to society was to commission a work of art on behalf of their family, their city, or their God. A person who hires, or commissions, an artist is called a Patron. Patronage enhanced a person’s or a family’s power and influence. Commissioning impressive art and architecture was also another way to “better” other rival families or city-states.

In European capitals, the Medici family had sixteen banking branches, which made them one of the richest families in the city-state of Florence. The family was also expert in earning the support of the less wealthy. Giovanni Medici, the founder of the family business, spent large amounts of money on churches and hospitals. As a powerful member of the city council (Signory), he sponsored tax reforms to help the poor by taxing more on the rich. Giovanni also sponsored lavish and elaborate celebrations in Florence, complete with parades featuring elaborate floats, ornately costumed characters, and giants on stilts. He was well liked and because of his generosity, even to the poor, most of the citizens of Florence mourned when Giovanni passed away.

Giovanni’s son, Cosimo, was even more successful at politics and business than his father had been. Cosimo established behind-the-scenes control of the government of Florence. The city council made him banker to Florence and special advisor to the government. With these offices, he basically ran the city of Florence for thirty years. Cosimo remained in power because he identified his own interests with the wellbeing of the people of Florence, mostly by patronizing the arts.

Like his father, Cosimo financed churches and hospitals for the citizens of Florence. Cosimo also spent money on extravagant palaces, expensive furniture, and ancient as well as modern works of art. He employed the greatest artists, craftsmen and architects of his day to make Florence a showpiece throughout Italy (as well as his own personal surroundings). The Medici family entertained on a large scale and paid for elaborate celebrations. Cosimo was so successful in establishing the Medici name that his grandson, Lorenzo, continued the family’s political control of Florence throughout another generation, without ever being challenged.

Lorenzo de’ Medici (or Lorenzo the Magnificent) was deeply interested in classical art, architecture, and literature. During Lorenzo’s lifetime, the Classical Age was reborn. This new vision of the world, now called the Renaissance by modern historians, began in Italy and spread throughout Europe all through the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Florentines already knew about the making of beautiful objects before the Renaissance. Since the Middle Ages, the city had been admired for its high quality artistry in gold, silver, and silk. The same workshops that had produced beautiful medieval gold jewelry or silver goblets had also prepared young artists for careers in painting, sculpture, or architecture. At the end of the fourteenth century, a new Renaissance Style in art began to emerge in some of these workshops. Art began to look more realistic, with highlights and shadow, as well as sculpture with human musculature. As great new talent emerged in these workshops, the Medici family quickly employed them.

During the Renaissance, for the first time in history, artists, sculptors, painters and architects gained respect in society. In earlier ages, these people were considered in a much lower social standing, the same as simple stonecutters or carpenters. They were not well educated or even well off. As the Renaissance began to unfold, the wealthy and powerful in Italian city-states competed with each other to hire the very finest artists available. The Renaissance was a time when the upper classes wanted to create an image of sophistication using architecture, personal portrait paintings, and sculpture.

The artists of this age were also shaped by Renaissance ideals. When they talked with their wealthy patrons, they learned that the creation of beautiful things was important and they learned about the philosophies of the Classical Age. As a result, talented artists began to see themselves as more than just craftsmen. They also began learning the history and stories found in Classical Age literature and gathered inspiration from classical sculpture, architecture and painting. These artists began to define themselves as “creators” as they experimented with new artistic ideas instead of “copying” art in the same unnatural styles of the last few hundred years*. Artists discovered a new self-confidence as well as a new respect from society. Some considered the greatest of these artists to be geniuses. Donatello, Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael are still given this same respect in today’s world.

*(In the middle ages portrait art was purposely created in a flat, unnatural, cookie cutter fashion, so as not to offend God in creating lifelike “graven images”. Art used in churches was intentionally unrealistic, used purely to teach the stories of the bible to people who could not read. As the middle ages advanced, artists began trying to create more realism in their art.)

Patrons—Those Who Commissioned Art

During Medieval and Renaissance times, artists were not in charge of art—patrons were. “Patrons” were clients who hired (commissioned) an artist, specified what they wanted painted or sculpted and commanded how much they would spend for the artist’s time and the materials. Patrons were generally considered the true “creator” of an artwork, not the artist. Patrons completely dictated in detail the subject and materials used in an artwork. The artists were originally just considered hired hands that executed the patron’s plan for the work, to achieve the patron’s goals. Contracts between patrons and artists were often specific in describing the quality and quantity of materials and could specify exact compositional details, such as the name of the Saint or the story of the scene that was to be painted. Patrons were people of power, high social standing and money.

During the Renaissance, as artists demonstrated their growing skills and talents, they came to be more respected as the creative force behind an artwork. Artists now gained esteem on the level of scholars or scientists, rather than simply as craftsmen (trained worker such as a carpenter, stonemason, butcher, blacksmith, etc.). A few geniuses, like Leonardo and Michelangelo, led the way toward a future where artists had great freedom to paint whatever they liked, in whatever way they wanted to. It is interesting that today, for most Renaissance art, the names of the patrons who commissioned the work have long been lost and forgotten, while the names of the artists are still known.

The wealthy princes of the Renaissance wanted the glories that only the greatest artists could provide—frescoed palaces and splendid monuments—so their admiration for the master artists who could create these magnificent works knew no bounds. Rich, aristocratic patrons helped elevate the level of artists in society and helped to lift the high level of artistic workmanship achieved during the Renaissance. There are stories of how Leonardo da Vinci died in the arms of the King of France and how the Emperor Charles V knelt to pick up the brush of Titian, the great Venetian painter—unbelievable because of the vast differences in social rank, until the Renaissance times. These traditional tales could be exaggerated, but they help to show the fact that a great artist of the High Renaissance was not considered merely the equal of a prince, but was somewhat held in awe as some miraculous gift of God.

Another powerful and well-to-do patron was the Catholic Church, an important political power in Italy and Europe. Pope Julius II was probably the most daring patron of the Renaissance. His plans for the beautification of Rome knew no bounds and he taxed the faithful to pay for it. Pope Julius II proposed to Michelangelo a plan for his own tomb. It was to be the largest and most elaborate sculptural and architectural mausoleum created in Europe since Roman times. Michelangelo took great care to design it and the Pope was pleased with his plan. It was never built, however, which upset Michelangelo, so he left Rome and returned to Florence. The Pope then demanded Michelangelo’s return to Rome. Florence, now the most powerful and beautiful city-state in Italy, refused to give him up. The Pope threatened to excommunicate the entire city, in other words, throw all the Florentines out of the Catholic Church. Yet, Michelangelo still refused to return, and two of the greatest powers in Italy seemed to be on the verge of war—over, of all things, an artist!

(One sad note in the life of the genius Michelangelo was that his father was always ashamed that his son had become an artist. To his death, Michelangelo’s conservative and snobby father felt that his son had lowered himself beneath his inherited social rank and brought disrespect to the family by assuming the occupation of a mere sculptor and painter. However, he did not mind living off the money his successful son loyally gave in support to his father and younger brothers!)

1. “Bust of Lorenzo de Medici” (MED ee chee) Painted Terracotta Bust, 26” x 23 ¼” x 13”.

15th or 16th century, probably after a model by Verrocchio and Benintendi

About the Subject

Lorenzo de’ Medici (MED ee chee), the extremely remarkable Statesman of the Italian Florentine Republic, was born January 1, 1449. “Lorenzo the Magnificent” (Lorenzo il Magnifico), as he was known to the citizens of Florence, was not only a smart diplomat and politician, but also head of a brilliant group of scholars, artists, and poets.

Lorenzo and his family had enemies. Other powerful families in Florence were jealous the Medici family had ruled so successfully for already two generations and wanted to take away the family’s power. Another powerful rival banking family, the Pazzi, schemed with others against the Medici. Lorenzo and his brother, Giuliano (JEW lee aw no), attended church in the Florence Cathedral, on the morning of April 26, 1478. Henchmen hired by the Pazzi family were hidden among the church congregation. A certain moment during the traditional church service was the agreed upon signal for the villains to attack the brothers. Giuliano was mortally wounded but Lorenzo, though hurt, escaped and survived the attack. This made Lorenzo even more popular in the eyes of the citizens of Florence. The Pazzi and their henchmen were severely punished. Lorenzo thanked the citizens publicly for their support by placing life-size wax statues of himself, produced under the careful supervision of the skilled artist, Verrocchio, in some of Florence’s churches. None of these wax sculptures still exist.

Lorenzo was devoted to his city and his people, as well as his family and the Roman Catholic Church. During his lifetime, the art and architecture of Florence made it one of the most beautiful cities in Europe. Florence had one of the most outstanding libraries of Classic Greek and Roman literature to be found anywhere in Renaissance Europe. Lorenzo carefully administered and paid for its compilation. He used his money, power, and influence to support learning and the arts and enabled some of the greatest artists of the Renaissance to develop their talents. Lorenzo was charismatic, tough, energetic, and passionate about the pursuit of art and learning.

Lorenzo’s life coincided with the high point of the early Italian Renaissance; his death, in 1492, marked the end of the golden age of Florence. The fragile peace that he helped to maintain between the various Italian states collapsed on Lorenzo’s death. Two years later, the French invasion of 1494 was the beginning of nearly 400 years of foreign occupation of the Italian peninsula. Though the Medici remained in power in Florence for several centuries, producing three Popes and two Queens of France, none of Lorenzo’s successors approached his range of interests and accomplishments or the generosity of his vision.

About the Art

The is a realistic Bust Portrait Sculpture of Lorenzo Medici. It was made from terra cotta clay. A Bust is a FULL ROUND sculpture depicting the head, shoulders and upper chest of a person. The National Gallery of Art was given the sculpture as a gift to the museum in 1943. For years it was believed that the bust was painted in different shades of brown. After ten years of scientific research on the statue, it was revealed that it was covered in accumulated layers of dirt and over-paint, which almost completely hid the orginal colors of the sculpture.

The museum carefully cleaned the sculpture and discovered Lorenzo’s face originally had rosy natural tones on his lips and cheeks. Traces of detailed beard stubble had originally been painted around Lorenzo’s mouth, still well preserved under the many layers of dirt. The beard stubble adds a sense of naturalism to the sculpture. Lorenzo’s previously drab blue and brown clothing has been transformed, uncovering an orginally vibrant red hat and scarf. He also now wears a colorful blue-violet tunic (shirt).

One result of the reasearch before beginning the restoration work was a reevaluation of the artist credited with its creation. Previously it was thought the art was the work of Florentine sculptor and painter Adrea de Verrocchio, the teacher of Leonardo da Vinci. Scholars now believe that the bust was created by an unknown Italian sculptor of the early Sixteenth Century, who based this masterpiece on an image created by Orsino Benintendi, an Italian Renaissance wax portraitist supervised by Verocchio (one of Lorenzo’s wax “thank you for the support” statues discussed earlier.)

The ancient Romans developed the art of bust portrait sculpture and, since in the early days of their history they had few trained stone carvers of their own, they employed skilled Greeks to work for them. Terra cotta busts became popular with the Romans because they were easier and less expensive to make. Ancient Romans of any importantance wanted a bust portrait made of themselves. Terra cotta busts were the most common form of ancient statuary found. Because Lorenzo loved ancient Roman and Greek sculpture, this terra cotta bust would probably have pleased him.

Terra cotta is a red clay that can be heated to remain strong. Simple reddish brown garden pots are created from the same material. (Bring in a common, unglazed terra cotta pot found in any garden shop. The small 4” size is usually only around $1.) Terra cotta is still used to form many types of sculpture today, especially yard art and flower pots, because it is so inexpensive. Yet sculptures created with this material have survived for thousands of years from many ancient cultures of the world.

What is a Portrait? An image of a person or an animal

Since there were no cameras invented until hundreds of years after the Reanaissance, the only way we know today what people looked like back then was through Portrait painting and sculpture. This portrait sculpture probably looks very much like the real Lorenzo. It is as if we can see back in time.

What type of MOOD does the sculpture create? Do you get any feelings about this very famous historical figure when you look at the portrait bust? Based on the looks of this sculpture, what do you think Lorenzo was like? In charge, fair, generous, intelligent, a good leader, popular with the citizens of Florence

What do we call a sculpture like this, which shows only the head, shoulders and chest? Bust

Project Idea

- Use clay to create a BUST self-portrait sculpture.

- Create a BUST of a famous person you admire.

- Create a BUST of the teacher/principal.

- Find examples of Renaissance fashions and additional Renaissance portraiture to show the class. Draw and paint a portrait of a wealthy man and woman wearing high fashion, 15th century Renaissance fashions. Pay attention to the variety of hats and accessories to be found.

Who was David and Why was He so Important to the People of Florence?

“To those who bravely fight for the fatherland the gods will lend aid even against the most terrible foes.”

(Carved long ago on a plaque behind Donatello’s Marble “David” sculpture in Florence, Italy)

The story of David is found in the Old Testament of the Bible. David was a teenage shepherd boy serving as a soldier for Israel. In the story, an invading army was doing battle against the Israelites. Their leader was a fierce and evil warrior, named Goliath, who stood more than eight feet tall.

The invading army was much larger than the Israelite army and wanted to steal their land. The invaders invited the Israelites to send just one of their leaders to a place between the two armies, to do battle with their leader, Goliath. At first, no one felt capable of confronting the intimidating Goliath. Then, young David volunteered to battle Goliath. His only weapon was a slingshot and a few stones. David said a prayer for strength, then left to bravely face Goliath.

Using his slingshot and only one rock, David hit Goliath so hard in the forehead that he fell to the ground. Then David took Goliath’s sword and cut off his head, which he carried back with him as a sign of his victory. David became a hero and eventually a powerful king of Israel. The story is considered a powerful lesson of the triumph of good over evil.

The young shepherd boy, who defeated the evil giant Goliath, struck a chord with the citizens of Florence, Italy. At the beginning of the fifteenth century, Visconti, the ruler of Milan, Italy, had tried to capture and take over Florence. His troops were threateningly close to Florence when, in 1402, Visconti suddenly died, his army retreated, and the Florentines were safe once more. The people saw this fortunate occurrence as God’s protection, and, with little justification, as a great victory. In the Florentine’s eyes, their small and virtuous “good guy” republic had defeated (with God’s help) the large forces of the “bad guy,” Visconti. The Florentines saw that their victory was very similar to the Biblical story of David. To them, the comparison was clear—goodness can triumph over strength. From the triumph over Visconti and beyond, the image of the shepherd boy David became one of the defining symbols for the city of Florence.

There are three very different sculptured versions of David, the heroic shepherd boy included in this packet. Each has different unique characteristics and all three represent historically significant and progressive changes in the styles of Renaissance sculpture.

2. “David” by Donatello. Carved Marble (Circa 1408 – 1409).

Donatello was born in Florence in 1386. He never married and had no children. He was older than Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael, the Renaissance artists featured in this packet with the same names as the Ninja Turtle crew. Donatello formed an early friendship with the young architect, Brunelleschi. When he was sixteen the two of them went to Rome and began a systematic study of the works of antiquity to be found there (architecture and sculpture from the Classical Age). When he returned to Florence, Donatello didn’t try to imitate the sculptural examples that he had been studying in Rome, but tried to rival the classical works with his careful observation of nature.

Donatello tried to give his works a “living” quality. He worked hard to develop extremely natural details in the expression, the pose, and even the arrangements of the folds of the clothing to achieve this. His work is dramatic and emotional. One writer of his day (Vasari) put it well when he wrote of Donatello’s work—“life seems to move within the stone”.

The son of a Florentine wool carder, Donatello became a member of Lorenzo Ghiberti’s workshop by the time he was 21 and was trained as a sculptor. (Lorenzo Ghiberti was another very famous Renaissance artist.)

This sculpture is the earliest work that can definitely be attributed to Donatello. It is a marble statue of the Biblical David and shows the clear artistic influence of Ghiberti, Donatello’s teacher, in its medieval style, but Donatello soon developed a more powerful style of his own.

This David wears clothing in a style similar to the Middle Ages, typical of the sculpture style taught in Ghiberti’s workshop.

Who can describe what David is wearing? David has a cape draped and tied around his neck. He wears a long sleeved shirt. Large stitching can be seen where the sleeve is attached at the shoulder and along the side of the shirt. His lower legs are draped in a long robe, open in the center, which is the only piece of clothing not typically medieval. This was probably Donatello’s attempt at creating a look from the time in which David originally lived, although there were no photographs depicting the actual styles worn by people of Old Testament times.

(Discuss in advance with the teacher displaying David’s head on the classroom screen so it can be seen in closer detail.)

What do you notice about David’s head? He is wearing a crown of leaves, a symbol of Victory. His eyes are blank; there is no detail carving on his eyeballs.

Why would Donatello have sculpted this crown of leaves on David’s head?

The sculpture represents David’s victory over the giant Goliath

Originally, the eyes of ancient Greek sculptures were painted to create realistic detail. In fact, the entire carved sculpture was painted. The paint did not survive over the many years these ancient sculptures had been buried, so renaissance artists (who did not have modern scientific equipment to discover that the sculptures had originally been painted in with the details) at first carved their own sculptures with the same empty eyes. Renaissance artists continually improved on their realistic sculpturing and also carved in the eye details, the way most modern day sculptors also do with their realistic sculpture.

What do you see at David’s feet? The head of Goliath, with a stone embedded in the forehead and David’s sling

The Lily and the brave shepherd boy, David, are both symbols of Florence. After this sculpture was carved, between 1408 and 1409, it was to be placed on top of the Florence Cathedral. It is believed that the sculpture was possibly too small to be seen from the top of the Cathedral, which may have been why the sculpture was transferred to the Palazzo della Signoria (the town hall, now known as the Palazzo Vecchio) seven years later. It was put in an alcove (an indent on the outside of a building purposely providing a display area for statuary) there, which was painted with a blue background and gold lilies. Behind the statue, several years later, this inscription was recorded on a plaque: “To those who bravely fight for the fatherland the gods will lend aid even against the most terrible foes.”

Compare Donatello’s two David’s faces. Which one seems to have the most personality and individuality? What makes them different from each other?

Can you think of any other heroes whose stories are commonly told about in our culture today? (List some of these on the board if you plan to do the project below, otherwise discuss the similarities of their stories with that of David.) Include the story of “Jack and the Beanstalk” which is also about a boy and a giant.

Project Idea

Choose a cultural hero to sculpt in clay. If it is a popular hero often seen on TV, in the movies, or in cartoons, make your hero in your own unique way. (Don’t make him/her look exactly like the one everybody sees all the time.) Think of two objects that represent your hero. For David, Donatello chose three symbolic objects to include in his sculpture—Goliath’s head, the embedded stone, and the sling. Include at least two additional objects in your sculpture that are symbolic of the hero you have chosen. The objects you choose will be important because you are going to create a very different and unique look of your own for your hero. People looking at your sculpture should be able to figure out who the hero is from the symbolic objects that you choose to sculpt that represent your hero. For instance, if you pick a Ninja Turtle, you might choose a pizza and a rat as your symbolic objects.

3. “David” Bronze Cast Sculpture (Details, Circa 1430) by Donatello.

About the Artist

Donatello is generally considered one of the greatest sculptors of all time. Many of his sculptures were Renaissance breakthroughs. He used his own vision to create figures that were the earliest and most lifelike seen since Antiquity. Donatello’s sculptural work was inspired by the many examples of ancient Greek and Roman Classic Sculpture, which he carefully studied and analyzed. It is well known that Donatello had a detailed and wide-ranging knowledge of ancient sculpture, more so than any other artist of the Renaissance did. But he worked hard to improve on the realism of his own work. This David sculpture was so real that rival artists of his day judged it as “incredible that it was not molded upon the living body”.

Donatello died in Florence in 1466, at about 80 years of age. He continued to sculpt throughout his entire life and lived long enough to enjoy his own legendary status!

About the Art

Bronze Sculpture is the type of Art most often seen today in public places. Ancient classic sculptors created full round bronze sculptures but the technique had all but disappeared during the Middle Ages. Renaissance artists were interested in reviving the technique. Since the ancient bronze sculptures came with no instructions for how to reproduce them, Donatello minutely studied the examples and experimented with the process.

What excited Renaissance artists about Classical Art was the way that the beauty of the human body had been reproduced in three dimensions. The features found in early medieval portrait art looked very similar from one sculpture to the next and correct body proportions were not understood. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, artists began finding a more realistic look for their sculpture portraits. It was not until the Renaissance that artists were finally able to do this well. Renaissance artists wanted to recreate lifelike realism following ancient classic sculptural examples that showed realistic individualism and depth. They did not want to just copy ancient sculpture though. Instead, they wanted to revive the classical artistic techniques to improve their sculptures, portraying life as it was lived in the modern and progressive era of the fifteenth century!

By 1423, Donatello had mastered the art of sculpting in bronze. His technique was to first make a reinforced model of the sculpture in clay that was then coated in perfectly finished, smooth wax. This wax model was then covered with an additional mold, attached to the model with metal nails and fitted with a series of channels, to allow the wax to flow out as the model was heated. Molten bronze was poured in to fill the empty space left by the melted wax. After the metal cooled and hardened, the mold was removed, revealing the detailed sculpture. Finally, the sculptor would file and smooth any rough areas to finish the sculpture. Donatello is credited with the revival of this bronze casting technique.

Sometime around 1430, he was commissioned to create a bronze statue of David, although who his patron was is not known for sure. The sculpture’s recorded history begins with the wedding of Lorenzo the Magnificent, in 1469, when it was located in the center courtyard of the Medici (MED ih chee) palace in Florence. The statue was later moved, after the Medici family left Florence in 1496, to the courtyard of the Palazzo Vecchio, where Donatello’s marble David was already located.

This David was the very first bronze sculpture since antiquity to be made in FULL ROUND and fully life size. Artists of the Classical Age wished the world of the future to see their great empires and people as powerful and dynamic so their art reflected this human image. Donatello modeled his sculpture after Classical Age statuary poses, which made a point to show off the healthy muscles of athletes by not covering them. The sculpture is so perfectly real it is idealized (more perfect than natural).

When Donatello first began sculpting, portrait sculpture and painting featured clothing covering the entire body. In the Middle Ages, people usually wore layers of loose clothing, with long sleeves to the wrist. To capture the human realism and detail of classic ancient sculpture Donatello did not cover David’s muscles. In the days of the early Renaissance, this sculpture of David was probably somewhat shocking for people to see from an artist of their day. Donatello was the first to completely capture the true, calm, and harmonious mood of ancient bronze sculpture and improve upon it. This bronze David is the most classical of all Donatello’s works.

Although the Bible story says that David refused to wear armor as he faced Goliath, it does not say that he fought without clothing. The Bible story also does not explain why Donatello chose to give David a hat and boots. People in Israel never wore hats like this and isn’t this a strange sandal style of boot David is wearing?

Can you see David’s big toe near Goliath’s chin?

Another confusing contradiction with the Old Testament story is that Goliath’s head, seen under David’s booted foot, is covered with a helmet. In the story of David and Goliath, the young shepherd boy used only one stone and a sling to slay the giant. If Goliath had been wearing a helmet, as Donatello has displayed in his sculpture, the stone would never have injured the giant. These mysterious details of Donatello’s David have never been convincingly explained and still leave an air of mystery about the statue. Look closely at these enlarged sections of the sculpture to see these extremely interesting and puzzling details!

Why is the COLOR of Donatello’s two David statues different? One is carved from hard rock (marble); the other was created with melted metal poured into a mold

Why do you think Donatello added this hat to his bronze sculpture? Encourage opinions from the class

Explain that David was still a teenager when he faced Goliath. The artist did not want David to look like a full grown adult. Which of Donatello’s two sculptures looks most like a teen?

Which of the two Davids looks stronger? Why? It is not that this David looks “stronger” but mostly that the other David looks slightly less realistic and therefore “weaker”.

Can you find the two symbols of victory Donatello displays in this version of David? The crown of leaves on his hat and the wreath of leaves under Goliath’s head

Where do you see TEXTURE? Who can describe more than one type of TEXTURE found on this statue? If kids need help with this question, ask them for words to at least describe the texture of the boots, hair, and skin.

Is this “IMPLIED” TEXTURE or “ACTUAL” TEXTURE? Three-dimensional sculpture has “actual” texture because it can actually be touched and felt. “Implied” texture is found in a two-dimensional painting, which relies on the illusion of texture.

Renaissance Artist Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci was born in the little town of Vinci, near Florence, in 1452. The artist used the name of this town for his last name. His grandfather raised him and as a young boy, Leonardo was extremely curious about life. He was always interested in learning about everything. As a boy, he kept sketchbooks with drawings of plants, flowers, insects, birds, and animals. His drawings helped him study and learn about things. Throughout his entire life, Leonardo kept sketchbooks filled with sketches of interesting people, ideas for future sculpture projects, detailed illustrations of plants and animals, and drawings of inventions or experiments. He drew detailed studies of the human anatomy, sketched designs for a submarine, a tank, a helicopter and the parachute. Leonardo left ten thousand pages of drawings, ideas, sketches and notes, all written backwards, that can only be read when held up to a mirror.

Among the many things Leonardo studied was the architecture of ancient classical buildings that could be found throughout Italy. Classical Greek and Roman architecture used many arches. Leonardo discovered just how strong an arch could be. As an engineer, architect, and city planner, Leonardo included arches in many ways when he designed canals, sewers, castle plumbing, and entire cities. He was once hired to design a gigantic shore-to-shore bridge to span a huge river in Turkey. His plan was a never before seen, two-arch support bridge. The bridge was never finished because the King who hired him stopped the project. He changed his mind because he thought Leonardo’s design could not possibly work. Since da Vinci’s plans for the bridge were carefully sketched and recorded in detail, modern architects have tested his plan and discovered that this early bridge design really would have worked!

Leonardo also designed many magnificent buildings that were never constructed. He invented fantastic machines for both peacetime and war. He was an engineer, musician, philosopher, physicist, botanist, anatomist, geologist, geographer, and aerodynamic engineer. He was not only interested in each of these fields but was considered an expert in them all. Many of the things he began were never completed. He was too busy working on more new ideas.

Leonardo lived alone all of his life. In 1517, he became paralyzed and King Francois I of France invited Leonardo to live with him. In the small Chateau of Cloux, he enjoyed great honor and the esteem of the king and court, filling his last years making notes and drawings about his lifetime of learning and discoveries. Leonardo died there on May 2, 1519, at the age of 67.

Project Idea

Create sketchbooks and give kids a “Leonardo” type of idea to think about, requiring them to use their imaginations for the first drawing. A suggestion might be a luxury car with not only highway, but also off-road, water, and air capabilities.

“He who loses his sight loses his view of the universe, and is like one interred alive who can still move about and breathe in his grave. Do you not see that the eye encompasses the beauty of the whole world? It is the master of astronomy; it assists and directs all the arts of man. It sends men forth to all the corners of the earth. It reigns over the various departments of mathematics, and all its sciences are the most infallible. It has measured the distance and the size of the stars; has discovered the elements and the nature thereof; and from the courses of the constellations, it has enabled us to predict things to come. It has created architecture and perspective, and lastly, the divine art of painting. O, thou most excellent of all God’s creations! What hymns can do justice to thy nobility; what peoples, what tongues, sufficiently describe thine achievements?” –Leonardo da Vinci

“Knowing how to see” (Saper vedere) became the object of Leonardo’s life and a name for his art and his science.

4. “Mona Lisa (The Gioconda)” by Leonardo Da Vinci

When he was a teenager between the ages of 13-15, Leonardo’s father took him to Florence to become an apprentice of the famous painter and sculptor, Andrea del Verrocchio (another famous Renaissance artist), for three years. By the age of 25, he was famous as both a painter and a man of science.

Leonardo felt that painting was the supreme form of art. His most well known paintings are the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper. Leonardo used what he learned from nature and science to make his paintings look real. He painted beautiful portraits and his strokes were so smooth you can hardly see a brush mark on the canvas. Unfortunately, many of Leonardo’s paintings were never finished.

Leonardo used dark shadows and highlights to help give a realistic feeling of depth to his paintings. Leonardo would not settle for a painting that was less than perfect. He would spend years working on a single painting, so he did not produce many works. In fact, only 17 of his paintings have survived and some of these are not finished. (He was also busy working for other people, such as the Duke of Milan, designing war machines, cities and other things like that.)

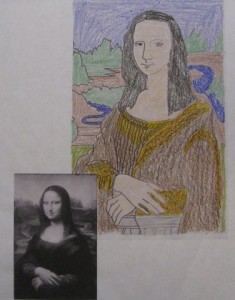

Leonardo spent four years painting “The Mona Lisa”. It is his most famous painting—in fact, it is considered the most famous and recognized painting in the world! You have probably seen “The Mona Lisa” before—in advertisements or on t-shirts. Even “Miss Piggy” has been used in a silly example of this famous portrait.

There are many special things about this skillful portrait. The paint has faded and cracked with time but the portrait once showed every detail, every eyelash. The painting is an almost eerie combination of a real-looking woman against a fairytale background. Her eyes almost seem to follow you around the room. No matter where you stand, the Mona Lisa is always looking right into your eyes. Especially eerie is that mystic smile—a hint of a smile that’s kept people talking for almost 500 years!

No one is sure who the model for Mona Lisa was. She is thought to have been the wife of a merchant named Francesco Del Gioconda, so the painting is more correctly known as “The Gioconda”. However, a new discovery about this painting has very recently developed. The self-portrait of da Vinci, drawn with red chalk in 1514, was compared to the Mona Lisa. The drawing was carefully laid over the top of this painting, using a computer so that the two pictures could be seen at the same time. The computer minutely measured things like the distance between the eyes. Many similarities were found between the two faces, especially the nose. Somebody must have been studying the two portraits very carefully to have thought of such a comparison. What do these similarities mean? It can only be guessed at but it is interesting to know that Leonardo kept the painting with him until his death.

Project Idea

- Draw and paint your own version of Mona Lisa. Update her clothing or her hair. She might be “fluffy and frilly” or a 1960’s flower child “Hippie”. The background could be very different and modern. How about skyscrapers and freeways? Rockets and Satellites? Let your imagination go wild!

- Study this portrait carefully to help you finish drawing the other half of Mona Lisa’s portrait.

Renaissance Artist Michelangelo Buonarroti

Michelangelo Buonarroti was born in a little town called Caprese, in the region of Tuscany, near Florence, on March 6, 1475. Michelangelo’s mother was very young and delicate. She found it hard to look after two small, demanding boys. Michelangelo’s father, Lodovico, was a dolce far niente, or the mayor of Caprese. He lost his job as mayor soon after Michelangelo was born and this made life difficult for the Buonarroti family. His mother decided to send the baby Michelangelo away to be looked after for awhile by a stonecutter’s wife. So Michelangelo spent an important part of his babyhood away from his home and his parents. There was another side to this arrangement that Michelangelo joked about when he was a famous sculptor later in life. His love for stone, he said, came from the tender care of the stonecutter’s wife.

Lodovico, Michelangelo’s father, could not concentrate on anything for very long and almost never held a proper job again. Poor Francesca, Michelangelo’s mother, had three more sons before she died in 1481, when Michelangelo was only six.

Michelangelo’s father, a snob all of his life, did everything possible to discourage his son from his growing interest in art. Michelangelo always had a stormy relationship with his father, who was often violently critical of his son and not at all affectionate. Yet, Michelangelo always remained loyal to him. During his lifetime, Michelangelo made many sacrifices to financially support his father and four brothers. Once he even wrote to his father saying, “All the troubles I have borne, I have borne out of affection for you.”

Despite his father’s negativity towards an artist son, at the age of 13 Michelangelo became apprenticed to Domenico Ghirlandaio, a very successful Renaissance artist (who lived from 1449 to 1494). A three-year contract had been arranged for him to work and learn there, but Michelangelo left within a year.

Michelangelo wanted to learn sculpture. The only place to study ancient sculpture in the city of Florence was in the Medici sculpture garden. A sculptor, Bertoldo di Giovanni (once a pupil of the great sculptor Donatello) was employed by Lorenzo de’ Medici to teach sculpture to young artists there and to look after the Medici (MED ee chee) collection of precious Classic Sculpture.

A story is told that one day, while walking in the gardens, Lorenzo Medici noticed and admired a head of a faun that young Michelangelo had carved (Faun: a character from classic Greek and Roman mythology, a deity represented as a man with the ears, horns, tail, and later also the hind legs, of a goat). Lorenzo remarked that since the carved figure was aged, it was strange that it still had all of its teeth. (In those days, there were no toothbrushes, toothpaste, or dentists. People’s permanent adult teeth often began to decay and fall out when they were only in their teens or twenties. Also, the only cure for a sore tooth was to pull it out, so old people—age 40 or older—often had many missing teeth.)

On a second visit to his sculpture garden, Lorenzo noticed that the young sculptor had taken time to drill out several of the faun’s teeth. Lorenzo was so impressed with Michelangelo’s talents and attention to detail that he invited him to live in his household, where he was treated as a son. Lorenzo became Michelangelo’s first patron and good friend.

At the palace of Lorenzo, young Michelangelo met and talked with the most brilliant group of thinkers that lived during the Renaissance. Although Michelangelo was deeply interested in their ideas, he never learned their polite and proper manners. He was rude, inconsiderate, and uncompromising as a young man and remained that way all of his life. One of the most powerful of all the Popes said that Michelangelo frightened him, and that he always greeted the artist while seated, since otherwise Michelangelo would rudely and improperly sit down first.

Michelangelo’s lack of manners did not win him friends as a boy either. While he was a young painting student under Ghirlandaio, he and a fellow classmate, young Pietro Torrigiano (who later became a renaissance sculptor), were sent to study the frescoes of Masaccio (mah sach ee oh) in the Church of the Carmine. While in the church, Michelangelo made a negative remark about a fellow student’s work. Young Torrigiano was so upset over the remark that he broke Michelangelo’s nose. For the rest of his life, Michelangelo’s nose looked like the nose of a prizefighter, a souvenir of his inability to get along with people.

6. “Pietà” (pea ay TAH). Carved marble. By Michelangelo Buonarroti.

When Lorenzo Medici (MED ee chee) died, Michelangelo was eighteen and already famous. He was not particularly happy with Lorenzo’s successor, Piero Medici, and left for Rome. It was in Rome that Michelangelo created the first of his two greatest sculptural works, the Pietà.

In Rome, Michelangelo met an elderly French Cardinal. A Cardinal is a man who works in the Roman Catholic Church. This Cardinal was about to retire and move back to France in his old age. He had lived in Rome for many years while he worked for the church and had grown to love the city. The Cardinal wanted to leave behind some type of beautiful monument in honor of the time that he had lived in Rome. The Cardinal hired (commissioned) the talented Michelangelo to create the special monument he had in mind. The Pietà was the subject the Cardinal chose for his monument. At the time, Michelangelo was just 23 years old.

What kind of MOOD or emotions does this sculpture create? Sadness, tragedy, loneliness, quiet reverence, pity, empathy from anyone who has ever lost someone important in their life

Can you feel the sadness the woman of the sculpture must be feeling?

A scene like this, whether created in a painting or in a sculpture, is called “pieta,” which means, “pity” in Italian. Paintings and sculptures on this subject were common among artists in Northern Europe, but it was an unusual sculptural subject for Italy.

The sign of a truly great and masterful artist is the ability to create strong feelings and emotions (MOOD) for people who view their artwork. Has Michelangelo been successful in creating strong feelings for viewers with his Pieta?

This famous sculpture depicts Mary, grieving over the body of Christ lying across her knees. We see Mary looking down at Jesus with quiet sadness. Her face appears calm but the single gesture of her hand helps show what must be the helplessness she felt not being able to prevent this tragedy. The lifeless body of a perfectly strong and healthy young man also helps to create emotion. We feel pity for this woman, which is what the title of the sculpture actually means.

When Michelangelo signed the contract for this marble sculpture, it was supposed to be finished in a year, but it took him two years to finish. By the time the sculpture was completed, the French Cardinal who commissioned the statue had already died and never knew what an amazing gift that he had given the world when he commissioned Michelangelo for the Pietà! This masterful sculpture amazed the people of Rome. The many folds of Mary’s dress drape as if they are made of limp fabric instead of stiff marble. The carved and polished veins and tendons in Jesus’ hands are extremely detailed and realistic. Since the Classical Age of the ancient Greeks, there had been no other sculptor with such amazing skill to create such large, lifelike reality from cold stone!

The sculpture was finished in the Holy Year AD 1500. Religious Pilgrims from all over Europe were traveling to Rome. These pilgrims toured the magnificent paintings and sculptures found in Rome that honored their religious faith. Michelangelo delivered his finished Pietà to Saint Peter’s Cathedral himself, in a handcart. He was annoyed when he overheard a man informing an admiring crowd gathered around his Pietà, that another Italian sculptor from Milan had created it. That night Michelangelo returned to the chapel with his sculpting tools. On the band that runs diagonally across Mary’s chest, the sculptor carved “Michelangelo Buonarroti from Florence made this”. (Point this band out to the kids.)

The sculpture was the first and only work of art that this artist ever signed. Michelangelo did not even put his artist’s signature on the famous and beautiful frescoes he single-handedly painted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel!

What do you think made Michelangelo go back to his finished sculpture, which was already on display, and sign his name? Probably his pride—the artist had a hard time controlling his temper.

Mary’s face is young—too young to be the mother of the full-grown man whose body she holds. When asked why he had carved Mary with such a young and beautiful face, the artist answered that physical perfection reflects Mary’s pure soul (or heart). Michelangelo was a religious man who held Mary in high esteem. She and Christ, across her lap, were both strong symbols of holy purity to the artist. The beautiful statue is a reflection of the artist’s great respect and admiration for both of these two.

When we look at Christ’s arms and legs, we can see the bulges of healthy veins and muscles, signs that this was someone still full of energy and a life surely cut short.

Describe the sculpture’s overall TEXTURE. The smooth marble is polished to high gloss sheen.

How would you describe the TEXTURE of Mary’s dress?

This sculpture was attacked and damaged by a crazed man several years ago. Fortunately, professionals were able to repair this almost 500-year-old sculptural masterpiece and it is displayed behind protective glass today.

7. “David” Marble, by Michelangelo Buonarroti (1501-1504).

About the Artist

Michelangelo returned to Florence in 1501, for his next commission. The political leaders of Florence wanted to celebrate the new peace that had come back to the city following several struggles over leadership after Lorenzo’s death. A huge block of marble, called “the giant”, had been stored for fifty years in a Florence Cathedral work yard. Another artist had begun to sculpt the marble block many years before, but had stopped because the large block had a dangerous flaw. The leaders of Florence held a contest to see who would sculpt this more than fourteen-foot block of marble. Michelangelo and Leonardo were rivals in the competition. Michelangelo showed the city officials a model of his plan for the block and three days later was notified that he had won. A shed was built around the block to give Michelangelo privacy while he sculpted for almost three years. He began work on the block of marble on September 12, 1501. The result was one of the largest and most magnificent works of sculpture ever created, depicting the young shepherd boy and Biblical hero, David, who slew the ferocious giant, Goliath. The sculpture made Michelangelo world famous.

Michelangelo remained healthy and strong, even into his old age. He rode horseback in the country every day, even in bad weather. He worked on his sculptures right up to the old age of 83, when he caught a fever after a horse ride in the rain, and died just a few days later.

About the Art

This is the second of Michelangelo’s two greatest sculptures. David is almost fourteen feet high and is now inside Florence’s City Art Gallery, although it was displayed outside in the main square of Florence for many, many years. Originally, the sculpture was to be mounted on the roof of the Florence Cathedral, but because the work was so perfect and beautiful, it was decided that the sculpture would be set in front of the Palazzo Vecchio instead.

The statue is idealized, just like Donatello’s statue. Who can explain what it means to “idealize” a sculpture? To make it more perfect than natural What else did Michelangelo do with his sculpture that was similar to Donatello? He did not cover David’s muscles.

The sculpture shows David with his slingshot over his shoulder, just before he faces the evil giant, Goliath. This David is also patterned after Classic Sculpture examples but the sculpture is much, much larger. Every muscle and every vein of this sculpture was sculpted with a physical accuracy that had never been equaled up to that time and its heroic size radiates dynamic power and energy.

The David sculptures created by Donatello show the subject after the battle with Goliath. Michelangelo’s sculpture shows David before the famous battle. What type of MOOD has the sculptor created in his portrait? David’s fear is disguised as being calmly brave and relaxed

The detail of David’s head shows the furrowed brow and determined expression of the young boy, which were understood by the people of Florence to represent the pride they felt in their great city. He is seen in a relaxed position, showing his courage, defiance, and his control of the dangerous situation. The dignity of the statue was a symbol for the dignity of Florence, the small city that had for centuries defied all the great powers that had continually threatened its independence.

Which of the three sculptures of David appears to be an older, stronger teen?

Renaissance Artist Raphael Sanzio

Raphael Sanzio was born in Urbino, Italy, on April 6, 1483. The Duke of Urbino wanted to make it a place of beauty with stunning architecture, sculpture and paintings. He wanted to show the rest of the world that Urbino was forward thinking, so he hired the best artists, architects, writers, poets and scientists to come there.

Raphael’s father was a successful artist who lived in Urbino. There are no records, but most people think he taught his son how to paint while Raphael was still very young. His father died when Raphael was only eleven, but his father was probably the one who arranged for Raphael to leave Urbino and go to the nearby town of Perugia, when he was 14-15 years old, to train in Pietro Perugino’s workshop. Pietro was a famous painter of the time and Raphael became one of his best students.

When Raphael was 19 or 20, he moved to Florence, Italy. Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vince were famous artists working and living in Florence at the time. By studying the works of Michelangelo, Raphael learned to show human movement much more naturally in his own paintings. Both great artists aided Raphael in improving his painting techniques. Raphael idolized the older Leonardo and managed to get along with Michelangelo, something many others could not accomplish. Raphael got along well with most people and was known as friendly, outgoing and charismatic.

His first patrons (customers) were those who actually wanted either Leonardo or Michelangelo, but settled for Raphael because both of these artists were too busy with other patrons. Raphael soon became a popular artist for his own abilities and people all over the city of Florence wanted to hire him.

Best known as a painter, Raphael worked in architecture as well. He was the favorite artist of Pope Julius II. Besides painting the palace room frescos, he became head architect of the new St. Peter’s Church. The Pope also made Raphael responsible for preserving some important ancient Roman ruins that had been freshly discovered at the time.

Raphael Sanzio died young, on April 6, 1520, exactly the same day of the year when he had been born.

8. “The School of Athens” by Raphael, Circa 1510.

Late in 1508, Raphael went to Rome and was hired to decorate the new apartments of Pope Julius II’s palace, located in the Vatican. Although he had never taken on such a project before, Raphael did not hesitate as he began painting some amazing frescos.

In the first room, Raphael painted a large set of frescoes representing the great branches of Renaissance learning—literature, philosophy, justice, and theology. He brought these abstract ideas to life by creating a fictional historic scene filled with imaginary portraits of Classical Age heroes representing the smartest teachers, poets, scientists, and mathematicians of ancient Greece and Rome.

At the top of the stairs in the center, are Plato and Aristotle, the greatest philosophers of the Classical Age. Other famous classic thinkers surround these two. Each character represents a specific historic person. The group of figures is divided into two categories—those that agreed with the philosophy of Plato on the left and those supporting the ideas of Aristotle on the right.

Since he did not know what those ancient people actually looked like, Raphael used people he respected from his own time as models. The philosopher Plato, seen center left with the white beard, is said to be a portrait of Leonardo da Vince. Can you find Leonardo (as Plato) underneath the center arch, on the left?

The ancient astronomer and mathematician Heraclitus (seated gloomily resting his head on his hand, in the left foreground) is said to be a portrait tribute to Michelangelo. This figure was not seen in Raphael’s early drawings for this work. Including this character is believed to have been in honor of the older master, after Raphael had seen the first phase of Michelangelo’s work on the fresco of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Do you see the figure believed to be modeled after Michelangelo?

Raphael used himself as a model, too. He is the young man way over on the far right, near the front, wearing a black hat and looking towards the viewer. Can you find Raphael?

The Process of painting a Fresco

A Fresco is a painting that covers an entire wall or ceiling and is painted on plaster. “True Fresco” is considered the noblest of all forms of painting. It is very hard to do and there is no room for mistakes. In this type of fresco, the pigment is mixed with water and brushed into the fresh, wet plaster of the wall. If the wall is too wet, the plaster won’t accept the color. If the plaster on the wall is too dry, the color won’t enter into the wall and the paint will later brush off.

Raphael had to know exactly how his finished picture was going to look before he began. He pre-drew his work, to wall size, on huge sheets of paper. This drawing, or pattern, is called a cartoon. The artist’s helpers then put pinholes along the drawn lines. To do this a special tool with a spiked wheel was used. Then the cartoon was placed against the wet plaster wall. Next, a pouncing bag, filled with powdered charcoal, was tapped over the punched lines and the outline of the drawing was transferred onto the wall in lines of dots.

Now the artist had to work quickly. The trick was to paint the wall during the few hours when the surface was just dry enough to suck the color in and just wet enough to combine its moisture with the set paint. When done correctly, the color and the wall dried together and became one. If the wall cracked, so did the fresco. Cracks in a true fresco are not disfigurements. They tell us about the life of the building and the painting.

The amount of surface a fresco painter could cover in one day depended on how difficult the design was and the artist’s own speed and physical endurance. He plastered just as much wall as he expected to cover in one day. The next day he would chip away any unpainted, dried plaster and apply fresh plaster in order to continue. This added to the length of time that it took the artist to finish a wall.

There was another problem for the fresco artist. As the plaster dried, the fresco colors lightened. It was very hard to mix the same color the next day to match. Wet color on plaster is darker. Raphael had to mentally remember what the color looked like before it dried so that he could create an exact match for the next day’s painting.

The fresco artist set daily goals for how far he would paint each day. He would try to end his picture at a point that wouldn’t be too noticeable. It is interesting that many of the cracks in old frescoes are where dry plaster and wet plaster had been joined.

Fresco Project Suggestion (Section from a Plaster Wall)

Create a section from a plaster wall using premixed joint compound spread very thinly over a piece of cardboard, Styrofoam, or foam core board. The thinner it is spread, the sooner it will dry to the touch. A low knap paint roller is recommended unless you have a professional sheetrock installer at home who will help. If you spread the plaster the night before your presentation it will still be moist enough to work with the next day. You do not want the plaster to dry out before it is painted. If possible, stack the fairly dry wall sections inside a plastic bag in the morning so that they will remain moist. It also takes at least an hour or two for the plaster to be dry enough to stack, transport, or paint on, depending on how thickly it is spread.

The larger the base you have to cover, the longer it will take for preparation time. This project takes more time than most in preparation but the results are highly impressive. At least a 10” square or rectangle for kids to work with is recommended. Paint with watercolor but remind class they don’t want to use too much water or it might damage the plaster or cause colors to run together. If the plaster is moist, kids will actually see the chemical process taking place that binds the paint with the plaster. If the plaster is dry it can still be painted nicely.

Kids can’t draw on the plaster before they paint. Pass out a piece of paper with the same dimensions for kids to practice drawing their designs before they paint. PAINT MOST OF THE PLASTER! Do not leave large areas of unpainted plaster. Remind kids to change water each time they change colors so that the colors will be bright and fresh. To make a color darker, use very little water in the brush. Paint the first layer of color quickly then move to another area. After everything has been painted, begin again where you started and add a second layer of color to areas that you feel need to be darker.

Painted plaster will dry in about 24 hours but the plaque needs to be set somewhere with good ventilation for at least 5 days. Dry plaster takes at least a week to “cure”. Be careful that moisture under the plaque does not damage what you set it on. Rotate plaque as it is drying to be sure the bottom dries quickly too.

9. “Saint George and the Dragon” by Raphael Sanzio

Raphael’s painting tells the story of Saint George, Patron Saint of Genoa and Venice (second to Mark), in Italy. St. George is considered the patron of soldiers, cavalry, archers and chivalry. He represents the virtues of courage, honor, and fortitude in defense of the Christian faith. His story represents the triumph of good over evil. The origin of the legend is obscure, there are numerous versions of the story, and many world cultures have similar legends. Although the details and locations vary, here is one version of the generally accepted story:

A dragon once lived outside a kingdom and would regularly fly over the city and surrounding fields, setting things on fire, such as crops used for food. He would eat livestock and generally ravage the kingdom, terrorizing the people. A bargain was finally struck with the dragon to leave the people alone. The trade was made for a daily meal of one sheep and one young girl in exchange for the dragon remaining in its cave.

A lottery was held each day for who would be the one in the kingdom to sacrifice either a daughter or a sheep. The king’s daughter was included in the lottery. Everyone figured this was a small sacrifice in exchange for relief from the daily threat to many more than this.

One day the king’s daughter was chosen in the lottery. The distraught king told his people they could have all of his gold and silver and half his kingdom if his daughter were spared; the people refused. The princess was sent to the cave to feed the dragon, just as all the other daughters before her.

Saint George, a valiant Christian soldier who fought for what was good and right, was traveling through the kingdom when he heard the story. He was determined to try to save the poor princess. When he neared the dragon’s cave, St. George saw a small procession of royal attendants, led by the princess dressed in beautiful silks, bravely walking towards the cave. He spurred his horse and overtook them. Comforting the princess and her attendants with brave words, St. George rode his horse towards the cave entrance as they watched.

As soon as the dragon saw George, it rushed from its cave roaring loudly and ferociously. Its head was immense and ugly and its mouth was filled with large sharp teeth. But Saint George was not afraid. He struck the monster with his lance, hoping to wound it. The dragon’s scales were so hard that the lance broke into pieces and the knight fell from his horse. St. George grabbed the sharp point of the broken lance, jumped back on his horse and rushed at the dragon. This time he pierced the dragon under its wing, where there were no scales. The knight continued to fight with his sword until the weakened dragon dropped from exhaustion. Saint George called to the princess to bring her belt to tie around the dragon’s neck. When the princess did, the wounded dragon followed her back to the castle like a dog on a leash.

The people saw the dragon coming and were terrified! The dragon was quiet as the princess and St. George stopped in front of the castle. The grieving king saw that his daughter was still alive and was overjoyed. St. George slew the dragon in front of the castle, to the relief of the entire kingdom!

Suggested Dialogue

What is the first thing that you see when you look at this picture? The horse and the knight

Point out the way the artist leads our eyes through the different parts of the picture using the COLOR red (MOVEMENT). Follow the red stripes on the broken lance to the saddle, to the muted red of the princess’s gown. This adds to the action of the scene and helps the viewer notice all the details of the story. Even if you had never heard the story of the painting, you could tell a basic story based on the details of the picture. This type of painting is called a NARRATIVE because it tells a story.

What sounds would you hear if you were standing in this painting? The roar of the dragon, the whinny of the horse, the clanking armor, the voices of the princess and the knight, the sound of the lance breaking into pieces then later piercing the dragon, the sound of the sword hitting the dragon’s hard scales

Can you think of any modern day characters that fight evil? Are any of these characters like St. George? In what way(s)? How are they different?

Younger kids will enjoy moving like a knight in armor. Ask them to mime mounting a horse. Kids (K-1) can also mime a dragon that walks, flies, and is generally ferocious. Kindergartners might enjoy acting out the story. Divide 1/3 of the class into heroes, 1/3 into dragons, and 1/3 can be princesses and royal attendants cheering them on. Tell the story in a way that when you mention St. George in the story, you can point to the group of heroes, who will bravely pantomime a knight holding his sword and say “I will slay the dragon!” The group of royalty can wave at the knights and say, “Thank you for saving me brave knight!” The group of dragons can snarl, grimace and say, “I am hungry and ferocious!” Word the story so that you can stop and point to each group, to repeat the words and actions several times, as you tell the story. Most ages will think this goofy drama is different enough from regular presentations to have fun!

Who in this painting is loathsome/noble, frightened/brave, good/evil?

This picture paints a moral that GOOD (in human form) will triumph over EVIL. How does COLOR show good and evil? Why is the horse white? Point out the contrast the dark color of the dragon. Can you think of a subtle way that movies and cartoons help the audience know who is the “good guy” and who is the “bad guy”? “Good guys” usually wear white hats and light colored clothing; “bad guys” wear black hats and dark clothing. How can you tell the knight is winning? Explain that it was thought to be a knight’s Christian duty to restore order to the universe. Does this dragon look like a terrifying dragon? How might the artist have changed him to appear more ferocious?

Can you find a shimmering halo? What type of TEXTURE can you see in the painting? Compare the rigid armor, leathery dragon, horse’s mane, leafy trees, feathery plume

Raphael used REPETITION to help organize the painting. How are the animals alike? Their poses and expressions are repeated. Compare the position of the animals’ forelegs with the pose of the princess’ arms; all are similar (repeated). Can you see anything similar in the turn of her head? Does her hair seem to mimic the knight’s cape?

Project Ideas

- Discuss how the knight, horse, and dragon are grouped together. Use clay to create a grouping of a person with real or imaginary animals.

- What happens next in the painting? Paint a Landscape with the same characters to continue the story. You do not need to create only the very end of the story. Several things happen after the scene pictured here.

- (K-1) might enjoy having you read the illustrated story of St. George and the Dragon, by Margaret Hodges (Little Brown, 1984). This book was a Caldecott Medal winner but is a little long. Plan a few places where you could shorten the story as you read. The entire presentation (for K-1) could use only this artwork with the story, or the story activity suggested above. Finish the presentation by sculpting, painting, or drawing dragons, which all ages would enjoy!

Packet Extra:

“Lady of the Sassetti Family” c. 1487-88 by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-1494) or brother Davide ~ Italian

Domenico Ghirlandaio created many different types of paintings but he made most of his money doing portraits. Ghirlandaio influenced future artists Raphael and Michelangelo.

His technical execution and sheer objective brilliance makes this particular portrait a very creative work of art. This portrait tells us nothing about the sitter’s character except for what we can deduce from her hairstyle, her clothes and her jewelry. These material things are given as much importance as her face. Most likely she is a wealthy woman, as of course only the wealthy would be able to pay a painter to paint their portrait.

Use this painting to demonstrate what earlier art looked like – contrast with

Michelangelo and da Vinci.

Gallery Label from the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

“Probably painted by Domenico Ghirlandaio’s brother Davide, the sitter of this striking portrait has been identified as the fifth daughter of the banker Francesco Sassetti (he had seven daughters in all). The occasion may have been her marriage to Simone d’Amerigo Carnesecchi in 1488. Her well-to-do clothes include a coral necklace with a gold pendant with a red stone and three pearls. The three-quarter view and the manner in which the bust is cut off, with the arms acting as supports, remind one of sculpted portrait busts.”