1.

2.

3.

4.

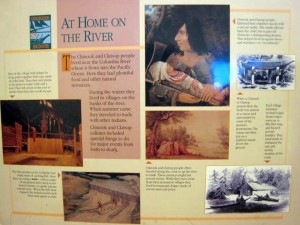

5. Poster—At Home on the River

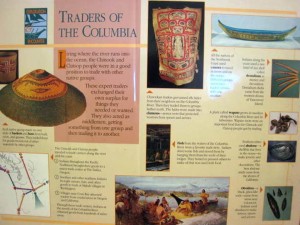

6. Poster—Traders of the Columbia

Packet Extra:

Sample Projects:

All four of these sculptures are CAST SCULPTURES. This means that the sculptor created the original sculpture from a different material and then created a MOLD, usually from plaster, clay and/or ceramic. Molten metal was then poured into the mold at a FOUNDRY. The metal was allowed to cool and harden. Then, the mold was removed from around the sculpture and the metal was either welded, or smoothed and buffed, to create a finished sculpture.

Most cast sculptures are created with Bronze, a mixture of copper and tin. Bronze can be bright and shiny, like a new penny, or very dark. It can also develop a natural “PATINA”, over the years, or the artist can create a PATINA by painting the metal with a chemical. A PATINA is a coating that can change the color of the metal. It can be a light green color, like the Statue of Liberty, or the chemical can be heated to create shades of oranges and pinks. The Pioneer Mother Memorial is developing its own natural PATINA. Pioneer Mother, ILCHEE, and the Horses were all cast in bronze. The bronze of ILCHEE and the Horses have a darker coloring. Two horses are brown and one is black. The Boat of Discovery is painted red, so we aren’t sure if it is cast from bronze, but it’s very likely.

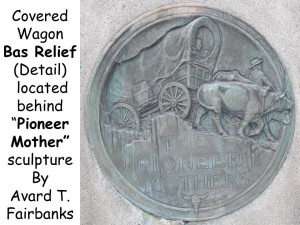

FORM is the Basic Element represented in Sculpture. TEXTURE is different in each of these sculptures. The definition of ABSTRACT should be discussed when viewing The Boat of Discovery sculpture. Discuss and define FULL ROUND sculpture (Ilchee: Moon Girl, Boat of Discovery, Horses, Pioneer Mother) and HIGH RELIEF sculpture (The covered wagon sculpture on the back of the Pioneer Mother Memorial).

What types of words might describe the MOOD for each of these sculptures? COLOR is different in each sculpture. Consider and discuss whether or not the MOOD of a particular sculpture would change if the COLOR were different. Did the sculptors choose the right color? What about a blue Pioneer Mother or a green Boat of Discovery?

Be sure ALL 6 pictures are returned to the Packet Carrier after your Presentation is finished.

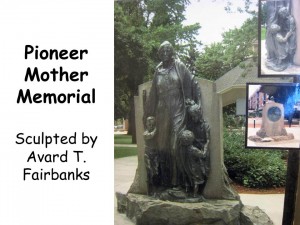

1. “The Pioneer Mother Memorial Statue” by Avard (AY-vard) T. Fairbanks.

Located in Esther Short Park—Downtown Vancouver, WA.

About the Artist

Avard Tennyson Fairbanks was born in Provo, Utah, on March 2, 1897. He was the tenth son in a family of eleven children. His father was an artist, who taught art at the Brigham Young Academy (now Brigham Young University) along with operating a photography studio, assisted by his oldest son. Avard’s mother, Lilly, wanted all of her children to be well educated but an accident, when Avard was barely a year old, prevented Lilly from seeing her hopes fulfilled. Lilly fell and injured her back in August of 1897 and remained bedfast until she died eight months later. Avard’s father, older brothers and sisters raised him, along with his younger infant brother.

Avard first showed interest in sculpture at age twelve, when his oldest brother (who was also an accomplished artist) taught him to sculpt. Avard chose his pet rabbit as his first model. The clay rabbit sculpture was entered in the State Fair and won first prize! When the judge, a university professor, found out the sculpture was the work of a boy, he refused to award Avard the medal. This thoughtless act caused more than a disappointment. It made the young boy resentful and determined to do even better work. He resolved to become an accomplished artist so that in time the professor would have to recognize him as a true sculptor!

When his father went to New York City, to paint copies of masterpieces at the Metropolitan Museum, Avard went along with him. He also obtained a permit to copy sculpture at the museum but it was reluctantly granted because he was so young. However, the Museum Curator apologized for his reluctance after he saw how well Avard could sculpt! A reporter for the New York Herald, who had observed him sculpting at the museum, wrote an article titled “Young Michelangelo of this Modern Day in Knickerbockers (the short pants younger boys used to wear) working at the Metropolitan Museum.” The newspaper article led Avard to other great opportunities.

In 1910 and 1911, Avard was awarded scholarships to study at the Art Students League in New York. During this time he became personally acquainted with several notable sculptors, often receiving advice and instruction from them. One of these sculptors was Gutzon Borglum, the designer of Mount Rushmore. Young Avard’s sculpture was displayed in the National Academy of Design while he was studying in New York and he was just 14 years old! This was a quite an honor. After a year and a half in New York City, his father ran out of work and money so they returned home to Salt Lake City, Utah.

Avard’s father recognized that his son had great artistic ability. He planned to make it possible for Avard to study art in Paris. During the next 2 years Avard and his father worked to obtain sculpture commissions that might finance the trip to Paris. All these efforts ended in disappointment, until Avard offered to sculpt a lion in butter for a creamery exhibit at the Utah State Fair. Avard’s sculpture attracted a large crowd and made the manager very happy. It also attracted other sculpture contracts, which finally earned enough money for Paris.

In 1913, Avard left for Paris to study Art. Some of his work was displayed in the Grand Salon of Paris but Avard’s Paris studies were cut short by the outbreak of World War I. He and his father had to return to Salt Lake City, where Avard continued his high school education. During this time (1915) young Avard modeled sculpture that was exhibited at the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco.

Avard and his oldest brother received a commission to erect four sculptured friezes (sculpture panel in high relief) in Hawaii. Other sculpture he did there included a bas-relief honoring Hawaiian motherhood. While he was in Hawaii, Avard sent for his sweetheart, Maude Fox. They were married in Honolulu.

After World War I, Avard and his wife toured the Northwest. He met Dean Lawrence of the School of Architecture at the University of Oregon. The Dean was impressed with Avard’s work and his training. An appointment as Assistant Professor of Art was made, in 1920, to teach sculpture at the University of Oregon, in Eugene. Besides organizing sculpture courses on that campus, he also taught courses on the campus in Portland, Oregon.

Avard’s creative works, while in Oregon, included “The Awakening of Aphrodite”, which is placed in the Washburn Gardens of Eugene. World War I Memorials in bas-relief were erected at Jefferson High School in Portland and at Oregon State University in Corvallis. “Guidance of Youth” stands in Bush Park in Salem, Oregon.

During 1924, Fairbanks took a leave of absence to study at Yale University. He returned to Oregon and continued as an assistant professor until he was awarded a fellowship that sent him to Europe to study and do creative sculpture. Most of Avard’s study was done in Florence, Italy. “Pioneer Mother Memorial”, for Vancouver’s Esther Short park, was completed and cast in bronze at a Foundry in Florence, Italy, while Avard was there on fellowship. Avard Tennyson Fairbanks died January 1, 1987.

Suggested Dialogue

“. . . [Sculpture] should be understandable to children, the untutored, as well as the most highly learned and technically trained. When our work is erected in public places for all to behold, we build an atmosphere and an environment. For this reason, masterpieces of sculpture, because of their very nature of attracting attention, evoke admiration. Our products therefore become great factors in large-scale education and community uplift and pride.”

Avard T. Fairbanks

This is a quote from the artist who created The Pioneer Mother Statue. How does this statue fulfill what the artist wanted his work to accomplish—“to educate us and give us pride in our community”? It could inspire us to find out more about Vancouver’s pioneer heritage. Visiting Fort Vancouver and Vancouver’s Museum, downtown on Main Street, could help us educate ourselves on the pioneer history of this area.

What type of sculpture is The Pioneer Mother? High Relief, it is attached to a background, although MOST of the sculpture seems to be free standing and full round. The sculpture is made of cast bronze.

What type of sculpture is the Covered Wagon, which is found on the wall behind the Pioneer Mother? Bas (pronounced Bah) Relief or Low Relief Sculpture, also made of cast bronze

Did you ever wonder what it would have been a child during pioneer times?

Why do you think that only the mother is shown with the children? Many families lost members of their family on the trail from accident or disease. Maybe this father traveled ahead of the family, to build a home for them, so the mother had to bring the family across the Oregon Trail alone.

Do you think it was hard for this mother and her children to travel west? Most of the trip was taken on foot. The wagon held supplies and belongings for their new home. There wasn’t really room for passengers and it wasn’t comfortable. There were no paved roads, only dusty trails that were often muddy and hard to travel on when it rained. Covered wagons had no shock absorbers, so the ride was very bumpy. The dust from the wagons in front made children choke and cough. There were no comfortable beds or motels to sleep in on the trail. There were no fast food restaurants to eat at. Camp had to be made, fuel for a fire had to be gathered and the fire started before dinner could be cooked.

Do you think that you would have enjoyed these conditions if you were traveling along the Oregon Trail as a pioneer child? Do you think the trip would have been more fun back then or today? Why?

What type of MOOD does the sculpture have? How does it make you feel?

Project Idea

• Draw or paint pictures of pioneers and covered wagons on the trail.

• Create covered wagons with small boxes and white construction paper. Cut wheels from cardboard and attach to the box with brads. Small milk cartons will work well.

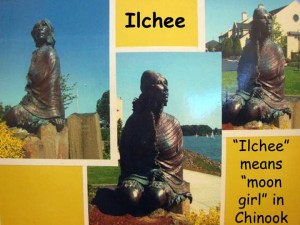

2. “ILCHEE” (Chinook for “Moon Girl”) by Eric Jensen, 1994.

* “History says she was born along the Columbia River about 1800, daughter of Chinook Chief Comcomly and later wife of Chief Casino, leader of the Vancouver area.

Lore tells us she had the power of a Shaman [a medicine man or magician] and that she paddled her own canoe, which was the sign of a chief. By both accounts, she was remarkable.”

*Information from plaque attached to the sculpture. There is a rock behind this plaque, which has Native American Petroglyph carvings. If you get the chance to visit the sculpture, see if you can find this Petroglyph rock.

Local Native American History Associated with the Sculpture

The bronze statue of princess ILCHEE is situated on the shore of the Columbia River, off Columbia drive, on Vancouver’s Waterfront. She is near the Columbia Shores Condominiums at ILLCHEE Plaza. ILCHEE was a real person in history. Her statue was placed here, in recognition of the people who had inhabited this region for thousands of years—The Chinook Indians.

There were several tribes in this area, with different Indian tribal names, but they could all be called Chinook. Local tribes were located by Lacamas Lake, where the Washougal River meets the Columbia River, and in the area where Ellsworth Road would meet the Columbia River.

The Chinook hunted and fished for food. They were not farmers but they used the plants that naturally grew here. They stayed here year round and wore animal skins to keep warm in the winter. Like many Northwest Native Americans, the Chinook lived in large cedar houses and many families lived together. Part of the house was underground. They cooked inside their huge houses. One of these homes has been discovered in the area and has been excavated and studied by archaeologists.

Each little tribe had its own language so they needed a common trade language. This language probably originated with the Chinook Astoria Indians, with a mixture of French and American English. Each tribe had things they would trade such as furs, salmon, shells and berries. This was sometimes done at the Potlatch.

Preparations for the potlatch would begin when a lookout from the tribe would spot the first Salmon coming up the Columbia River. The three-day celebration would include a feast, business, dances, engagements, trading, etc.

The Chinook were extremely prosperous merchant lords of the Columbia River. Yet, by the 1830s, they were a devastated people. Overhunting (loss of food sources due to the fur trapping for trade), alcoholism, and finally disease (which killed nine out of ten Chinook) were the result of the coming of “civilization” to the home of the Chinook.

About the Artist

Sculptor Eric Jensen lives in Scappoose, Oregon. In the late 1980’s, on his way to finding his niche as an artist, Jensen decided to create a line of sculptured fantasy figures. Jensen designed a swordsman, a sorcerer, a dragon and a few other small sculptures of these make believe characters. He had originally intended to raise the standards of hobbyist sculpture by creating his own graceful and realistic works of authentic art for hobbyist modelers to purchase. Jensen soon gave up on the idea, though, due to the lack of copyright protection for this type of art and because the commercialism of this type of product seemed to cheapen the value of the art. Yet, before Eric Jensen was finished with his artistic experiment (hobbyist modeling), he molded a little Asian Geisha statuette. The girl was pretty, with a very serious expression, with one hand gripping a short sword hidden beneath a slit in her kimono.

A couple of years later, Jensen altered that small Geisha sculpture into a Chinook Indian Princess, as part of a contest the city of Vancouver was presenting to celebrate the arrival of the British Sea Captain who became the city’s namesake. Jensen didn’t win the Captain Vancouver contest with his Chinook Princess sculpture, but a couple of years later, city leaders asked the sculptor to build his monumental statue in a plaza in the center of a redevelopment project for Vancouver’s Columbia River waterfront. This area is now called ILCHEE Plaza.

The bronze statue of ILCHEE (Chinook for “moon girl”) is situated on the shore of the Columbia River. ILCHEE looks like she is relaxed and gazing out towards the sailboats traveling along the river on sunny days or at the lighted Christmas ships that travel there in winter. The seven-foot-tall, 700-pound bronze sculpture has become one of the city’s icons since it has been erected. Artist Eric Jensen still cleans and polishes the statue himself, at least once a year. He won the Governor’s Arts and Heritage Award, from the Washington State Arts Commission, for creating the sculpture.

About the Art and Suggested Dialogue

ILCHEE wears a nose-ornament, which originally would have been carved from a shell. Because she was an important woman, it is elaborately carved. Her nose ring looks like a long, thin fish. The fish’s head and tail seem to meet, forming the ring. Shell nose-ornaments were common to many of the Northwest Indians tribes but they struck the British newcomers as extremely different from the costumes of any other Native Americans they had ever seen.

The large square earrings ILCHEE wears would have been created with abalone shell. This shell was considered valuable to the Indians. Abalone is not found in this area and could have only been obtained from trade, which is one reason that it was so valuable. Do you think those large earrings would have been heavy? If you have access to a piece of abalone shell, let kids see and feel how thick and heavy it is.

ILCHEE’s cape would have been woven from cedar bark. The cedar bark repelled the rain that is common in our area and a woven cape like this was used as an ancient raincoat. Northwest Native Americans used the soft yellowish fiber, just underneath the hard outside cedar bark, to make a type of rough yarn (similar to Raffia). Only a small part of the bark would be removed from a cedar tree at one time, so it would not kill the tree. The fiber was dried, shredded and twisted into a type of yarn that could be woven. ILCHEE’s basketry cape would also have been lined with animal fur and fastened with a fish bone. The Portland Art Museum owns a real cedar bark cape like this.

ILCHEE’S skirt (which we can only see a little of) would have been made of cattail reeds. This type of skirt is similar to the idea of a Hula skirt. The skirt has a very different TEXTURE than the cape; although woven cedar bark skirts were also very common among the Northwest Coast Indian tribes.

Notice the shape of ILLCHEE’S forehead. Does it seem differently shaped than yours? It is! Her forehead is very flat which makes the top of her head seem a little pointed. Chinook Indians admired a flat, smooth forehead and to achieve this they practiced head shaping. This painless process was done in the first year of a child’s life when the skull can be easily molded. It was accomplished by putting the infant in a special cradleboard (papoose), bound tightly against the baby’s forehead. (See Poster At Home on the River for explanatory illustration) ILCHEE’s hair, like the hair of other Chinook women of her time, would have been slickened with salmon oil to keep it shiny.

Project Ideas

• Write a paper about what ILCHEE is thinking as she gazes out at the boats and people who walk past her at the edge of the water. Is she comparing the way people dress today with the way her people dressed about 200 years ago? What does she think of the bike riders, skateboarders and people on roller blades moving past her? What about the music the teenagers play on their CD players as they pass? Does this seem strange to her? Does she like the music? What does she think of the colorful sailboats, water-skiers, and large barges, pushed by tugboats that often pass? Is she sad things have changed or is she excited by these modern new things? What does she think were the best and worst things about these two times of history? What does she think of our culture compared to her own?

• Challenge 4th and 5th graders to do research on ILCHEE and find out who her first husband was and what he did. (Chief Casino was her SECOND husband.) Offer a small reward for those who research this and write their correct answer (including name) on a piece of paper to hand in to you when you return next month. (Refer to “Glimpse into History through Sculpture” on next page for this information. Read sections of the article aloud to the class if nobody correctly answers this challenge on your next visit.)

• ILCHEE’S cape was made from woven cedar bark. Older kids could do a weaving project using Raffia, easily found in craft stores, to weave a small mat on a cardboard loom. Woven Raffia would resemble woven cedar bark.

• Younger kids could weave a mat using an 18”x24” piece of construction paper. Fold the paper in half to a 9”x12” size. Cut lines starting at the fold to about ½” from the outside edge. Unfold the paper and lay flat. Weave 1”x12” colored strips through the cut lines. Glue the ends of the strips to the ½” edge of the cut paper.

Glimpse into History through Sculpture

Although ILCHEE is mentioned relatively briefly in the 1805 journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition, her life fascinated local sculptor Eric Jensen enough to create a monumental bronze on the Columbia River in her likeness. In celebration of the sculpture’s 10th anniversary, in December 2004, Jensen looked back at his research on the Chinook Indians and ILCHEE and shared some of the highlights [featured below]:

The Chinooks were a dominant regional tribe in the early 1800’s, composed of a loosely allied chain of people strung along the shores of the lower Columbia River. They belonged to the Athabascan language group, meaning they migrated to this area from what is now British Columbia, many centuries before the Europeans arrived.

…The Chinook were slavers and traders whose territory extended from the Lower Columbia to San Francisco Bay. Mostly, they traded slaves from the south and Dentalium shells from the Vancouver Island area [to the north]. Dentalium shells were used to make wampum (a form of money) and wearable wealth, prized widely among all North American Indian tribes. The Chinook traded with tribes as far east as the Sioux and became wealthy in the process. They were most powerful near the mouths of the Willamette and the Columbia Rivers. ILCHEE’s father, Chief Comcomly, was the most influential of the Chinook leaders, and her mother, Princess Sunday, was his most favored wife.

ILCHEE was a girl when Lewis and Clark came through this area, and since she was the favored daughter of the most important wife, she was taken to meet the explorers, as recorded in their journals. A few years after the Lewis and Clark Expedition was when ILCHEE’s life became better documented and historians could form a better picture of her.

After the Astor Colony was created, in what is now modern day Astoria, ILCHEE was arranged to marry the colony’s Chief Factor, Dunchan McDougall. It was a troubled union from the beginning, and ILCHEE reportedly compared her husband publicly to a pig. McDougall eventually abandoned ILCHEE and their child to settle in Canada. Control of the young woman was returned to her father, Chief Comcomly. A pioneer family at Fort Vancouver, meanwhile, adopted the couple’s child.

Comcomly then arranged for ILCHEE to marry his rival, Chief Cassino, who controlled the Vancouver area, a strategically vital junction of trade and trailheads. This marriage did not last long either. It ended when Cassino’s baby from another wife died while under ILCHEE’s care (apparently from the flu). The death of a chief’s child, according to Chinook culture, must be avenged, so Cassino had assassins kill ILCHEE, according to the autobiography of explorer and educator Ranald McDonald, who was ILCHEE’s nephew.

“ILCHEE’s name translates to “moon girl,” and various historical accounts characterize her as beautiful, smart and sharp-tongued”, said Sculptor Eric Jensen.

The artist added that many of the comments he gets about the piece relate to its precise ethnological detailing, particularly in regard to the basketry cape that she is wearing. “Usually, Indians are depicted with the Plains’ fashions (feathered headdresses and the like),” he said. “But buckskins would have mildewed around here. Basketry was much more suited to this climate. I was trying to get [maximum] authenticity, so it really resonates with me when people talk about those kinds of details.”

He added, “I think of [ILCHEE] as a proud figure, looking out over the river, with her head up, her chin up. She’s a little exotic. But that’s what makes her special. That’s what makes her unique. I think that’s what resonates with people.”

A former mayor of Vancouver, Bruce Hagensen, oversaw the push in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s to create more interest in the Columbia River waterfront and provide more public access. “We were hoping to stimulate exactly what has happened,” Hagensen said. “I think [ILCHEE] showed to the community what lovely additions public art could be to our public places. It also symbolized that we were making a strong investment in our waterfront, in providing public access and in telling our history… We wanted to reach out to the Native Americans. We wanted to give them their long-overdue recognition. We wanted to say that we not only had an English fort here, but we also have a Native American history that goes back thousands of years.”

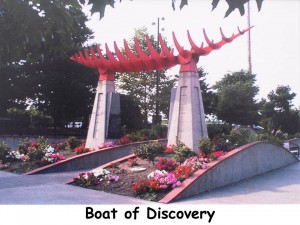

Boat of Discovery

3. “Captain George Vancouver Monument”

“October 31, 1792 Lieutenant William Broughton named this area for his Captain.”

Dedicated October 31, 1992

Captain George Vancouver, from King’s Lynn, England, at age 35 and with orders from the British admiralty to explore and chart the West Coast of America, charted hundreds of miles of coast line from California to Alaska. His maps were so accurate that they were later used in establishing boundaries between the Spanish, the English, the Russians and the Americans.

During the return voyage of his expedition, Captain Vancouver commissioned Lt. William Broughton to enter the Columbia River in long boats to explore inland. It was during this venture that the area was proclaimed in the name of England and was charted in honor of Captain George Vancouver.

Some 32 years later, in 1824, Dr. John McLoughlin and Sir George Simpson, of the Hudson Bay Company, using the accurate journal and map published by Captain George Vancouver, established the first permanent settlement in the Pacific Northwest and named it Fort Vancouver.

Lt. William Broughton explored and charted the Columbia River from a 24-foot long boat. The exploration some 100 miles inland commenced from the H.M.S. Chatham on October 23, 1792. The exploration party returned past this point [sight where plaque is located today near Vancouver “Quay” restaurant] October 31st enroute to the mouth of this great river. During his journey, Lt. Broughton named many of the natural features he saw including Mt. Hood and Mt. St. Helens. He named this area [Vancouver] for his Captain, George Vancouver.

*A replica of the map that Lt. Broughton created is etched on a plaque near the “Boat of Discovery” sculpture. The map of the river route is an example of “Sunken Relief”; the map is cut into the stone of the plaque. The above information is printed on this plaque. The following information is printed beneath the sculpture:

. . . “The real story of George Vancouver and other explorers of the Pacific Northwest is not in one great voyage. It is in the hundreds of lesser voyages made by the small boats, thoroughness and unfailing courage with which these tasks were carried out through the long years of exploration of the Great River of the West, the Columbia River.”

Suggested Dialogue

Does this sculpture look like a boat Lt. William Broughton traveled in to explore this area in 1792?

This boat is an abstract representation of a Long boat. That means it isn’t realistic. It appears as just the skeleton, or framework, a representation of a boat. It is not a scale representation of the size of a real long boat either. A ship of Lieutenant Broughton’s time would have been much bigger, with large masts and sails. The Long boat was a smaller boat than a ship—24 feet long. Probably no one knows for sure exactly what Broughton’s boat looked like, since cameras were not around then.

How can you tell this is a boat if you don’t look at the name of the sculpture? The sculpture’s lines are the general shape of a ship outline or the skeleton of a ship. There just isn’t a “skin” on it.

The title of this sculpture is “Boat of Discovery”. It is a monument to Captain George Vancouver.

Did Captain Vancouver take the longboat down the Columbia River? No, Lt. Broughton did but he was following the orders of his Captain and he named Vancouver in honor of his Captain.

Project Ideas

• Create an abstract *stabile sculpture from cardboard that resembles the FORM of this abstract boat sculpture.

• Create a clay sculpture of a boat.

• Create a poster board sculpture of a boat.

*See Evergreen School District Elementary Art Resource Guide (“Form” chapter) for instructions to build a stabile sculpture. Each school has a copy of this notebook. Tell your school’s Art Discovery Coordinator you are interested in checking out the instructions for this project in the resource guide. This is an excellent resource for any projects teaching the Basic Art Elements (color, line, texture, pattern, shape or form).

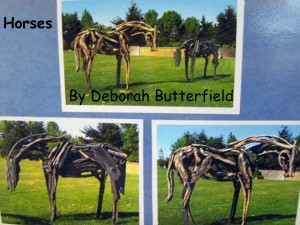

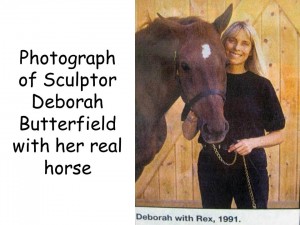

4. “Horses” by Deborah Butterfield

You can see these horses every time you leave the Portland Airport parking area, headed towards I-205. After you leave the tollbooth, the road curves to the left and you can observe these three life size horses as they stand grazing in the grass, on both sides of the road.

About the Artist

Deborah Butterfield was born in San Diego, California in 1949. She has devoted her career to exploring the image of the horse. Deborah has been fascinated by horses since childhood and created her first sculpture of a mare (female horse) in 1973, using plaster over a steel armature. Over the years, Butterfield has created horse sculptures using many different types of materials. While her sculptures seem more Expressionistic, these horses have a remarkable sense of realism. Deborah is an experienced horse trainer, which helps her sculpture seem more animated, since she has an intimate of knowledge of the natural posture and movement of horses.

About the Art

The horses are bronze sculptures. A bronze sculpture is created using a mold with hot metal poured into it. The mold is usually made from ceramic. A sculptor creates a sculpture using clay or other material first. Then the sculpture is covered with thick layers of plaster. The plaster is then cut in half and the original sculpture is taken out of the mold. The two sides are used to create a ceramic mold, with both sides joined together so it is hollow and enclosed. Metal is then melted into a liquid and poured into the mold. After the metal cools the mold is removed and the metal statue is left.

Butterfield first created an “assemblage” sculpture. This means that she assembled pieces of wood to create the original sculpture. Each individual piece of these sculptures (the pieces of wood) was cast separately and then welded to create the statue. This is what makes the wood pieces appear so realistic, if you look closely at the statue.

The Portland Art Museum owns a Deborah Butterfield Horse also. It was created differently, using bent tree limbs with the bark removed. Challenge kids to visit the museum with their parents and ask to see the Deborah Butterfield Horse sculpture!

Suggested Dialogue

Do these horses look realistic? When you first looked at them could you tell they were horses?

What do you think they are made of? They look as if they are made of driftwood, bark and one horse looks like a 2×4 piece of lumber supports one of his rear legs. If you walk up and look at them closely they seem as if they are made from different pieces of wood but if you knock on the wood you will realize that the statues are really made of metal cast and painted to LOOK like wood.

Has anyone seen these horses before?

Be sure to point out how Deborah’s horse FORMS have areas you can see through. Discuss the difference between FORM and SHAPE.

Project Ideas

• Gather small pieces of driftwood, twigs and large chunks of bark. Using tacky glue and fine pieces of florist wire, to connect the wooden pieces, let kids sculpt an animal. The pieces of wood can be stacked and glued with a small dot of tacky glue and then wired with small pieces of florist wire until they dry. Elmer’s Glue is too thin for this project. Have kids set their sculptures on paper plates to dry.

• Give kids pipe cleaners or pieces of heavier florist wire to create a wire sculpture of a horse.

• Create a horse sculpture using small and large marshmallows with toothpicks. (Great for K-1)

• Create a sculpture using a metal armature. A simple armature could be created using a drilled 2”x4” square with threaded spool wire. This type of project requires much more preparation time. The armature could be covered with clay or paper mâché.

5. “At Home on the River”

This large poster has written information about the Chinook and Clatsop Indians who were native to the Northwest area. The chook and Clatsop lived near the Columbia River where it flows into the Pacific Ocean. Here they had plentiful food and other natural resources. During the winter they lived in villages on the banks of the river. When summer came they traveled to trade with other Indians.

This poster features illustrations that include:

• A painting of the interior of a Native American Lodge. Men of the village build lodges by tying poles together with rope made of cedar bark. Then they tied planks to the poles to make walls and a roof. They left a hole in the roof so smoke from their fires could escape.

• Native American fishermen using a weir—a fence made of sharpened poles stuck in the stream bottom—to guide salmon toward traps. When the fish were trapped the Indians could catch them with spears or nets.

• Painted profile of a NW Native American woman holding her child in a cradle. Chinook and Clatsop people flattened their children’s heads with a special cradle. The cradle did not hurt the child but it gave all Chinooks a distinguishing feature which they felt was highly attractive. The slanted forehead of the Chinook woman pictured here was the result of the gentle pressure of the top of the cradleboard against a baby’s soft skull. This silhouette helped Chinook to recognize slaves and outsiders—or “roundheads.” (The sculpture of ILchee has a head that resembles this portrait.)

• A painting showing a Native American woven mat lodge can be seen. Chinook and Clatsop people often traveled along the coast or up the river to trade. These journeys might last several weeks. While they were away from their permanent villages they lived in temporary lodges made of woven mats and poles.

• Drawing of a grave memorial is also pictured. When a Chinook or Clatsop person died, the body was placed in a canoe and surrounded by some of the person’s possessions. The canoe was then put on a platform raised above the ground.

• Drawing of a small gathering of NW Native Americans. Each village included several lodges. Some lodges were up to fifty feet long and housed several families. They were made to with stand the rain and stormy weather of the coast.

6. “Traders of the Columbia”

Living where the river runs into the ocean, the Chinook and Clatsop people were in a good position to trade with other native groups. These expert traders exchanged their own surplus for things they needed or wanted. They also acted as middlemen, getting something from one group and then trading it to another.

This poster features illustrations that include:

• The Chinook and Clatsop people traveled to trade centers along the river and the coast. The map on this poster shows the direction of trade and is numbered:

1. Indians throughout the Pacific Northwest brought their goods to a major trade center at The Dalles, Oregon.

2. Nootkan and other northern Indians brought canoes, hats, and other goods to trade at Makah villages in Washington.

3. Villages near Coos bay attracted traders from coastal areas in Oregon and California.

• Each native group made its own style of baskets and hats from bark, roots, and grasses. They traded these for goods woven out of other materials by additional groups.

• Chinookan traders got tanned elk hides from their neighbors on the Columbia River. Then they traded them to groups farther north. The hides were made into clamons—armor vests that protected warriors from spears and arrows.

• All the natives of the Northwest Coast used canoes to travel in rivers and on the ocean. Different groups sometimes traded canoes with one another.

• Indians along the coast used a rare kind of sea shell called dentalium as money and decoration. Dentalium shells came from the western shores of Vancouver Island.

• A plant called Wapato grows in marshes along the Columbia River and its tributaries. Wapato roots were an important food that the Chook people got by trading.

• Northern tribes used abalone—a shellfish that lives in the ocean—to make jewelry and other decorations. The best abalone shells came from the shores of California.

• Fish from the waters of the Columbia River were a favorite trade item. Indians dried some fish and stored them by hanging them from the roofs of their lodges. They boiled or pressed others to make oil that was used with food.

• Obsidian—a black, glass-like rock—came from areas near volcanoes. Indians used obsidian to make knives, spears, and arrows.

At the bottom of the poster is a painting showing Native Americans trading along the river with a boat, their horses and many trade goods. By projecting this small picture on the large classroom screen the kids may be able to better see it.