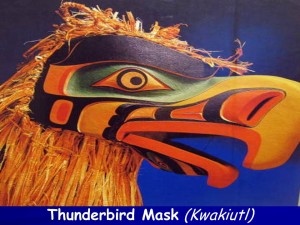

1. Thunderbird Mask by Dwayne Simeon

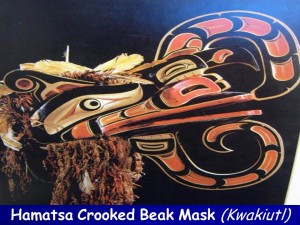

2. Hamatsa Crooked Beak Mask by Willie Seaweed

3. Frog Cape by Dempsey Bob, Linda Bob and Virginia Bob

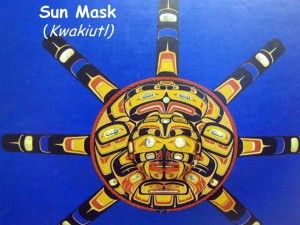

4. Sun Mask by Kevin Daniel Cranmer

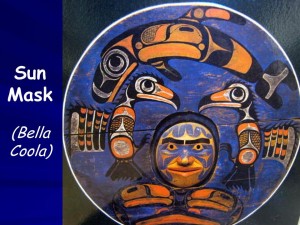

5. Sun Mask by Unknown Artist of the Bella Coola Tribe

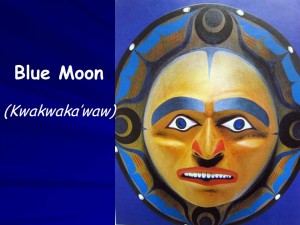

6. Blue Moon by Klatle-Bhi

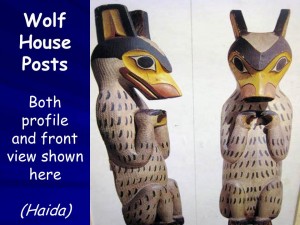

7. Wolf House Posts by Unknown Artist of the Haida Tribe

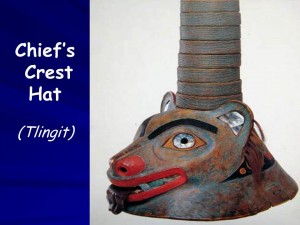

8. Crest Hat by Unknown Artist of the Tlingit Tribe

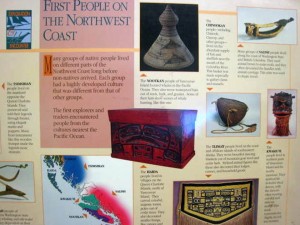

9. Poster—First People on the Northwest Coast

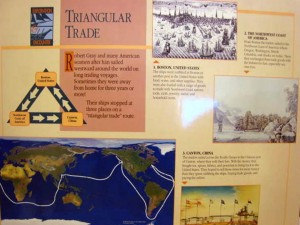

10. Poster—Triangular Trade

Packet Extras:

Sample Projects:

Northwest Native American Art is created using some unique and unusual design elements, which are not found in Fine Art. In this type of art, abstract animal designs are created using FORMLINES, OVOIDS, and U-FORM elements. Black form lines are filled in with various ovoid and U-Form elements, mostly painted red with white highlights. The carved and painted subjects are native animals that are also representations of various family crests or totems. Different colors are used to show the inside of the animal’s body—white, green, blue or yellow. These stylized designs are usually SYMMETRICALLY BALANCED.

The Native Americans who lived on the Pacific Northwest Coast dwelt in tribes or groups of related families. They believed that everything, from pebbles on the beach to animals, possessed a spirit.

Each clan (extended family) traced its origins to a specific spirit, which became their totem (symbol or crest). The sea and land animals that lived on the Pacific Northwest Coast formed the basis of First Nation mythology. Each clan had a story of how an ancestor had a special encounter with an animal or spirit. Consequently, they gained the skill to hunt certain animals, or the rights to hunt in a specific place or wear a special mask, or use an animal as a crest or totem for their art. Pictures of these spirits were carved on totem poles and masks and were sewn on robes. Traditional color schemes and stylized shapes were used to paint these spirits which were usually animals. Each spirit or animal had a story to go with it.

Be sure ALL 10 pictures are returned to the Packet Carrier after your Presentation is finished.

Northwest Coast Native American Art

The Northwest Coast Native Americans legends and art forms go back at least 1,000 years. The very simple DESIGN ELEMENTS used in the wonderful masks, totem poles, rattles, storage boxes, panels and other artistic objects were always used in a correct manner and specific rules had to be followed. These design elements are still used in the same way today by Northwest Native Americans. The design elements are based on specific types of SHAPES. You can easily tell what the ABSTRACT (Expressionistic) animals are if you understand the rules concerning the shapes of the design elements and the colors that are used.

Formline: A design system of the northwest Coast cultures in which thick and thin lines enclose the basic Ovoid and U-form elements and their variations.

Ovoid: Variations of an oval SHAPE (2-D) or FORM (3-D) used in the design system of Northwest Coast art

U-form: Variations of a U-shaped element in the design system of the Northwest Coast art

Animals represented in NW Coast Native American art have body parts that are enclosed with thick and thinner black lines called FORMLINES. Certain SHAPES and FORMS are used to show the different body parts of an animal. One frequently used element is called an OVOID. It is a variation of an oval and has a rounded top with a flat bottom. The ovoid may be solid (colored in with black or a color) but is usually an open shape made with a black Formline contour. The upper section of the Formline is usually thicker than the lower. A large ovoid may be used to create the head of a creature or a human. Ovoids can represent eye sockets or major joints of a body (knees or hips). They can help form a wing, tail, fluke, or fin. Small ovoids may contain faces or indicate eyes, ears, noses, or the blowhole of a whale. Ovoids also serve to fill empty spaces of a design.

Sometimes an INNER OVOID or a FLOATING OVOID is included inside a larger ovoid Formline. This ovoid may be small and solid (painted in with black), or a nearly solid element (including additional LINE and/or COLOR) representing an eyeball. Floating ovoids may also be part of the design on a wing, an arm or a body.

Another frequently used element is the U-FORM. It looks like the capital letter “U” and one leg may be longer than the other. Large U-Forms often help shape the body of a bird or an animal. U-Form can be seen as part of the Formline in ears and in the tail or flukes of a whale or fish. Smaller U-Forms also serve to fill in open spaces and are often used to represent the small individual feathers of a bird’s body.

Many times a SPLIT U-FORM is used in ears, feathers, tails and many other open spaces. If the U-Form is rather wide, a pair of Split U’s might fill the space in better.

FORMLINES are usually painted BLACK. U-forms and ovoids are most often painted RED, with white highlights. Individual form elements are placed closely together and often show the entire body of the animal. Sometimes only the head is shown.

The designs are frequently SYMMETRICALLY BALANCED (a mirror image on each side if divided down the center of the design).

Different colors are used to show the inside of an animal’s body, such as white, green, blue or yellow. These shapes and colors are used over and over again in different ways, depending on the animal depicted in the family legends. Stories that are told, sung and danced use these visual symbols that help the tribes and clans understand the ways of their ancient people and remember their cultural heritage.

Major Tribes of the Pacific Northwest

Tlingit (pronounced KHLING–git)

Tsimshian (pronounced SIM-shee-an)

Haida (pronounced HIDE-ah)

Heiltsuk (pronounced HEILT-sook)

Nuxalk (pronounced NU-Hauk)

Kwakwaka’wakw (pronounced Kwah-kwah-HOOAH-kwah)

Nuu’chah’nulth (pronounced Nou-CHAR-nooth)

Kwakiutl or Kwagiutl (pronounced KWAH-i-tl)

Bella Coola

Bella Bella

Nootka

An Assortment of NW Coast Tribal Tales

The Birth of Thunderbird

Toolux, the South Wind, always traveled north in the summertime. Feeling tired and hungry after a long day, he stopped to rest on the bank of a river. An old witch called Quoots-hoi lived in a stone house nearby.

Toolux said to her, “Give me some food, for I am very hungry.”

“I have nothing ready,” said the witch. “But here is a net. If you go and catch a little whale and bring it to me, I will cook it for you.”

Toolux took the net, which was made from the roots of the hemlock tree and waded into the water. He soon caught a little what and brought it back to the witch’s house to clean and get it ready for cooking.

Quoots-hoi handed him a knife made from a sharp seashell and said, “Do not cut it across the back, but split it along the backbone.

Toolux was in such a hurry for his dinner that he paid no attention to what the witch said and cut the whale across the back. The whale immediately changed into a huge bird and flew away into the mountains where she built a nest and laid her eggs.

Toolux and Quoots-hoi followed the bird and found the nest. They destroyed all the eggs except one, which hatched before they could break it. The chick that hatched from that egg was Thunderbird.

Thunderbird flew away to the top of another mountain that was covered with clouds so that no one could find him. Ever since, he has lived in the mountains making the thunder and the lightning

Tribal Whale Trivia and Mythology

Many legends and beliefs grew up around these great sea mammals. The Tsimshian (SIM-shee-an) saw whales as being members of four clans, and represented them differently in art design. This concept may have come from them recognizing that there were various whale species. The Eagle clan of the whales had a white stripe across the middle of the dorsal fin. The Wolf clan carried a long dorsal fin like a wolf’s tail. The Raven clan’s fin resembled a raven’s beak and the Gispawadwe’da (no translation) had a short fin with a hole in the center

The Mahkah (Muh-KAH), who lived on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington, and the Nootka actively hunted the gray whale. They were the only people along the entire Northwest Coast who hunted whales.

It was believed that if a whale were injured but not killed in the hunt, it would return at some other time and capsize the whaler’s canoe. A widespread belief was that a whale could capture a canoe and drag it and all those aboard down to the underwater village of the Whales. Once there, the people would be transformed and become whales themselves. The Haida (HIDE-ah) believed that whales appearing in front of a village were drowned persons returning to communicate with the people. Both the Tlingit (KHLING-git) and Haida Nations believed that great chiefs might return to life in the form of killer whales.

All of the Northwest Coast Nations use Killer Whale as a crest. Killer Whale can often be shown held in the claws of Thunderbird. In Northwest Native American Art he has a long dorsal fin and short pectoral fins. Killer Whale has a round, snouted head with a large mouth and many teeth. Sometimes he is shown with no teeth. The tail of the whale has SYMMETRICAL flukes (the same on each side).

The Tlingit story tells of ancestors visiting the undersea home of Killer Whale, where he gave them the right to use the killer whale as a sign of the tribe. The tribe was then endowed with that animal’s characteristics and its image was used as a crest. This right was passed on from generation to generation as a valuable possession, just like a house or a canoe.

The Haida have a legend of Raven-Finned Killer Whale, a Whale Chief who carries a raven perched on top of his tall dorsal fin. There are legends of two, three and even five-finned killer whales. These legends may have originated from the sight of a cluster of dorsal fins where a pod of whales surfaced together.

Natsilane and the Killer Whale

Natsilane was a master carver and the best spear-maker of the Grizzly Bear tribe. He tried hard to please his wife’s family—on sea lion hunts, he was always the first to leap out onto the rocks to make a kill. By the time his brothers-in-law arrived, all the other animals had escaped into the water.

Natsilane’s reputation as a hunter made his brothers-in-law so jealous that they plotted to get rid of him. Next time they went out on a hunt, the brothers paddled the canoe away and abandoned him on a rock. Only the youngest brother cried out for them to go back.

Natsilane tried to spear a sea lion to eat, but the spearhead broke off inside the animal and it swam away. However, the sea lions took him to their den, where he saved the sea lion chief’s son by removing his own broken spearhead from the animal’s side.

As a token of his thanks, the sea lion chief sent Natsilane home in an inflated sealskin bladder. Natsilane stopped at a beach near his village, chose a piece of spruce wood and set about carving a killer whale. His first attempt wouldn’t float, so he tried with hemlock wood and then with red cedar. Finally he carved a killer whale from yellow cedar, which leapt into the sea and swam.

Natsilane told the whale to find his brothers-in-law and drown all but the youngest. When this was done, he ordered the whale to do only good to humans in the future and so the killer whale became an omen of good luck.

Some Frog Tales

The Haida (HIDE-ah) are said to have carved a frog on a house pole to prevent it from falling over. It was also their belief that Raven ate frogs.

Frog’s characteristics are a large mouth, usually with thick lips, and legs (with toed feet) posed in a flexed position. The absence of teeth, ears and tail confirms frog’s identity.

Until they were introduced recently, there were no frogs inhabiting the Queen Charlotte Islands in Canada. Here are two different legends that might explain why:

North of the Queen Charlotte Islands, the Tlingit (KHLING-git) Chief’s daughter made fun of a frog and was later lured into the lake by a frog in human form. The chief’s daughter then married the frog. Unable to persuade the Frog People to let her return home, her father (the Chief) and her mother dug a ditch to drain the lake, which scattered the frogs in every direction.

Another tale explains that when the Frog Chief first encountered a black bear, he was terrified. The huge bear tried to step on the hopping creature for fun but the frog escaped. He returned to his village and told of the frightening experience. Fearful that the bear would seek them out, the frogs decided to flee the islands.

Wolf Tales and Tradition

Wolves were believed to have strong supernatural powers, but their spirits were harmless to humans. Revered because it was a good hunter, the wolf was often associated with the special spirit power a man had to acquire to become a successful hunter. A wolf is sometimes shown with flippers instead of paws. This is the mythical Sea Wolf, named Wasgo, from Haida (HIDE-ah) legends.

Both the Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwah-kwah-hooah-kwah) and Nuu’chah’nulth (Nou-char-nooth) Nations claimed wolves as ancestors and impersonated them in their ceremonies. The Wolf Dance of the Nuu’chah’nulth—the Tlokwana—records the days when the wolves taught the people to live together in communities and gave them the organizations that were important in First Nation society.

The creation story of the Nuu’chah’nulth (Nou-char-nooth) tells how an ancestor visited the House of Wolves, where he was taught songs and dances. He thought he had been away for four days, but when he went home he discovered that he had been gone four years.

Usually the wolf is seen in profile (from the side). He may be crouched on all fours or sitting with his front paws raised. The four main features that identify a wolf are long snout with flared nostrils, large and many teeth (which may include canines—those sharp front teeth), large ears and a curled-over tail. The tail might even have a lot of diagonal curved lines to represent its bushiness.

Why the Wolves Dance—A traditional Tribal Drama

The Tlokwana, or Wolf Dance of the Nuu’chah’nulth (Nou-CHAR-nooth), begins when men disguised as wolves kidnap a group of young children, wearing ceremonial costumes. The kidnapping is symbolized by finding the children’s ordinary clothes torn to pieces on the beach.

The parents of the kidnapped children are accused of being careless: “You should watch your children more carefully, then the wolves couldn’t steal them.” As a punishment, the parents are pushed into the sea.

Much feasting and merry-making follows this event, because it’s forbidden for anyone to eat alone during the ceremony.

In the early hours of the morning, search parties go through the village looking for the children, tipping people out of bed and throwing cold water over them. When the search proves fruitless, preparations are made to attract the wolves by ceremonial drumming.

The drum leader climbs onto the roof of the clan house to watch for supernatural signs that the drumming should begin. Soon the sound of whistling wolves can be heard outside the house. The drummers stop and the kidnapped children can be heard singing songs about how they have been captured by the wolves. The children are then taken away again.

Now the rescuers set out in canoes across the bay, armed with traps made of twigs and netting. After several feigned attacks and a great deal of hilarious jostling, the children are “rescued” and returned to the village. They perform the songs and dances that the wolves have taught them and their ceremonial costumes are burned.

Native Americans felt that children were special and important. They were supposed to be protected and cared for until they were grown. Tribal children became full fledged adults as teenagers.

Does this story give you any clues about how important caring for children was to the NW Coast Native Americans? The dance probably helped the tribe’s children know that they were an important part of the village. Everyone probably had some good laughs after sleeping grown-ups were tipped out of bed and splashed with cold water. The dramatic “rescue” sounds like a lot of fun and good laughs for the entire village. This tradition seems like a good excuse for adults to play games!

Careless parents are pushed into the sea as punishment for not watching out for their children, after men in wolf costumes pretend to kidnap them. What message would this dance give to the tribe’s parents? That it was important to take good care of their children

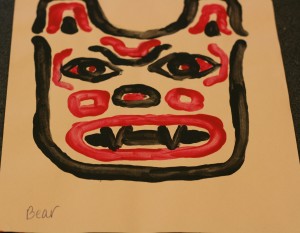

Bear Mythology

Marriages with animals, particularly bears, occur often in traditional NW Indian stories. The bear was thought to have a close relationship with people because it behaves like a human and competes for the same food. It can walk on its hind legs, fish for salmon and eat berries. When chasing a bear, a hunter carried out a special ritual, because he was killing a creature whose soul was so much like his own.

In Native American art the bear is defined by having short, round ears, large flaring nostrils, a wide mouth with conspicuous teeth and often a protruding tongue (it sticks out). Claw-like hands and feet are characteristic. The small tail of the bear is usually ignored and not included in artwork.

In the Tsimshian (SIM-shee-an) village there is a tall totem pole carved with the figures of a mother bear and her cubs. Its legend tells the following story. Other clans had their own version of the bear myth but most of them followed this theme.

The Girl Who Married a Bear

One late afternoon, Peesunt, the daughter of the chief, was picking huckleberries in the woods. Peesunt stepped in some droppings left by a bear. “Ugh,” she cried in disgust, “what filthy, disgusting creatures bears are!”

Soon afterward, a handsome young man wearing a thick bearskin cloak came walking toward her through the woods. “Come,” he said, “give me that heavy basket. It is much too late for you to return home now. My village is not far from here. You can stay there tonight.”

He led Peesunt to his village, where a number of people were seated around a fire, all wrapped in bearskin robes. An old woman at the center of the group said, “Your insulting words have angered the Bear chief. He sent his son to bring you back and now you are to become his wife.”

So Peesunt had to marry the chief’s son and soon she gave birth to twin children who had human form in their own home, but changed into bears whenever they went out.

Back in Peesunt’s village her family was grief-stricken at her disappearance and her brothers searched for several years to find her. They hunted many bears all over the country until, at last, they found the cave where Peesunt was imprisoned and killed her husband.

Peesunt went home and was greeted with much rejoicing. Her children, though remaining human from then on, were able to kill bears with ease, because they were related.

Sun and Star Mythology

Northwest Coast Native Americans believed that the arrival of daylight transformed creatures into the physical forms they are today. People who were wearing the skins of otters, beavers or seal, turned into those animals when Raven let the sun loose. Those who were wearing nothing remained as human beings. They selected their clan crests (or totems) in memory of their transformed animal companions who had once been humans. Here is the traditional story of how daylight came to the world:

How Raven Stole Daylight

When Raven was born, the world was still in darkness. Far up the Nass River lived a selfish chief who kept the light just for himself.

Raven thought of many plans for getting light into the world. Finally he changed himself into a hemlock needle, which then fell into some water that the chief’s daughter was about to drink. The girl swallowed the needle and raven was inside her. Raven was then born to the chief’s daughter in the form of a baby.

When her baby was born (who was actually Raven), he gazed around with bright eyes. He pointed to some bundles hanging on the wall and cried for several days until finally his grandfather said, “Give my grandchild what he is crying for. Give him that one hanging on the end. That is the box of stars.”

The child that was Raven played with the box, rolling it around on the floor. Suddenly he threw it up through the smoke-hole. The box flew up into the sky and the stars fell out, arranging themselves as they are today.

Sometime later he began crying again. Then his grandfather said, “Untie the next bundle and give it to him.”

As before, Raven rolled the box around on the floor and after a while he threw it up through the smoke-hole—and there was the big, silvery, full moon for all to see.

Now there was just one bundle hanging on the wall and so Raven cried for that. As soon as he had the box in his hands he uttered a raven cry, “Caw, caw,” and flew out through the smoke-hole.

Raven tried to exchange the sun box for food, but he was only mocked for his efforts. So he opened the lid of the box anyway, and the sun burst out and rose into the sky.

The Potlatch

Potlatches are held to mark many important occasions in the native tribal cultures of the Northwest. These can include the naming of a child, the coming of age of a chief’s daughter, a marriage, the raising of a totem pole, a memorial ceremony for a dead chief or the taking of an additional name by a chief, giving him more prestige. The important part is that the occasion happens before witnesses and is accompanied by feasting and the giving of gifts. A chief, who is generous providing lavish gifts and hospitality, is highly thought of by his clan and by neighboring villages. Potlatches were an important institution on the Northwest Coast in ancient times and thousands of dollars in goods, including blankets, food and ornaments, could be distributed by a tribal leader to rival clans. The challenge to the other clans was to match or top this show of generosity. The Potlatch is still important to modern Northwest Native Americans.

Potlatches have a set plan of events. A modern Potlatch lasts 12 to 14 hours. In the past they could go on for days and days.

A Potlatch always starts with a mourning session. The Potlatch giver asks women to come before the assembled chiefs and pay tribute to those who have died recently and their departed ancestors.

If a copper is to be sold or transferred, this is done next. This is a very solemn event. Coppers are large plaques of copper metal sculpted with designs of a clan’s crest. Coppers are used as an indication of wealth—they generally are valued at the same cost as the number of blankets given away at the Potlatch. To throw only one copper down in front of a chief was a great insult.

If a marriage ceremony is to be performed, this happened next. Then the great feast, including the tseka ceremony, when cedar bark headdresses are distributed to the chiefs. Feast songs are sung, and ceremonial dances are performed. After the feast, guests join in am’lala or “fun dances”. Lastly, gifts and money are given to the guests in order of their social rank.

In 1884, the Canadian Parliament outlawed the Potlatch, in a move to discourage the continuation of Native culture. In the opinion of the Canadian government and church officials, Indians engaged in “heathenistic” dances and cannibalism. Although there was a “Cannibal” dance done at some Potlatches, it was only part of a pretend dramatization. No Native Americans actually participated in any real cannibalism.

For the first few years, the law was not enforced because there wasn’t enough money to send Indian Agents to investigate possible violations. In the 1920’s, government officials began cracking down on Potlatching and there were many arrests throughout the following 30 years. During the years the Potlatch was outlawed, many Northwest Indian cultures lost much of their traditional heritage. Traditions were passed to younger generations through observation and participation in the annual ceremonies, songs and dances of the Potlatch. Masks were carved for ceremonies of the Potlatch, and since the Potlatch was banned, there was no reason to carve masks or to teach the younger generations how to carve them. Because of this, when the old people died there were few left to carry on the stories, dances, songs and traditional arts, since the traditional place for their use had been the Potlatch.

Many Potlatch ceremonies still occurred during the 1920’s and 1930’s, although they were changed. The Potlatch had originally lasted for several days. After the potlatch was outlawed and Potlatch celebrations had to be secret, they began to last only 12-14 hours. The tribes that continued to carry on the Potlatch in secret were able to pass the traditions, stories, artwork and dances down to the younger generations and their traditional culture was not lost. Many tribes lost their cultural heritage because they followed the new government’s law and did not hold traditional Potlatches. When the older members of these tribes died, the tribal traditions died with them.

During the 1940’s, much Northwest Native American heritage was maintained and encouraged through illegal Potlatches but, as young Indian men went to serve in World War II, a significant change began. These soldiers returned with a transformed perspective on life. Many of them began to move away from their villages to work somewhere else. Many left to join the civilization that had grown up around their ancient villages. The ancient traditions were being left behind and forgotten by this younger generation. The potlatch law was amended in 1951. Tribes were no longer forced to hide this traditional event. Many Northwest tribes still celebrate the Potlatch traditions today.

Thunderbird Mask

11” x 30”

Dwayne Simeon

1997

About the Artist

The modern artist who created this mask is a Kwakiutl (KWAH-i-tl) Indian. He was born in 1960 and now lives in Vancouver, British Columbia. Dwayne says, “Listening to our elders stories about our old culture and our history of devastation, I realized how rich our culture was and all that we have lost. I awakened to my responsibilities and to the need to revive our art and our culture. Being an artist is what I was meant to do, to keep our art, our stories and our culture alive.”

About the Art

In the legends of the First Nations of the Pacific Northwest Coast, thunder and lightning have great symbolic significance. Several stories tell of a giant mythical Thunderbird with supernatural strength that inhabited the mountain peaks. When this large creature flapped its huge wings, there was a terrific roar of thunder and lightening shot out from its piercing eyes and beak. Whenever storms came up, people were reminded of the power of Thunderbird.

Each different tribal group had its own legend about Thunderbird. The Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwa-kwa-HOOAH-kwa) Nation tells how Thunderbird helped another ancestral spirit to build a large house. Thunderbird then transformed himself into a human and so became the founder of that family.

When Thunderbird was hungry he ate whales. Thunderbird grasped the two Lightning Snakes that lived under his wings and threw them down onto a surfacing whale. The snakes, striking with their lightning tongues, killed the whale. Then Thunderbird swooped down, picked up the whale in his mighty talons, and flew with it to the far mountains to eat.

Thunderbird appears mainly on Kwakwaka’wakw and Nuu’chah’nulth (Nou-CHAR-nooth) totem poles. The bird is usually depicted with outstretched wings. The Thunderbird has curled horns on its head. The horns are a way to identify the designs of Thunderbird and Raven because the two birds sometimes appear very similar.

The mask was carved from cedar, with shredded cedar bark added to the top and back of the head, and under the chin. If you look closely at the eye you can see the wood grain. The bottom half of the beak opens and closes. The mask is 11” tall and almost 30” wide.

Suggested Dialogue

Do you think this mask would be heavy to wear?

Can you point out any U-FORMS or OVOIDS on the mask?

Project Ideas

- Make Thunderbird masks by attaching a construction paper beak to the bottom of a paper plate. Notice how the tip of Thunderbird’s beak is curved. Fold yellow construction paper in half the long direction. The fold will be the top of the beak. Draw the curve at one side of the fold and cut from the other side, like the wide part of a triangle. The tip of what would be the triangle is now the curved beak. It won’t have a fold. Fold the opposite edge of the beak horizontally about ½ “ and cut 6 slits across this area. This will form tabs. Attack beak to plate at the tabs so it becomes three-dimensional. Tape or glue curve of beak together at top and front. Use red, black and white construction paper to cut eyes, Ovoids and U-Forms. Glue on mask to decorate. Attach string or elastic to the sides of the plate so the mask will hang on the wall or for kids to wear.

- Create a paper mâche Thunderbird mask and paint with tempera paint. This is a larger project that will require one or two more construction times to finish. Some volunteers traditionally do one big project each year.

Hamatsa Crooked Beak Mask

Artist Willie Seaweed (Kwakiutl Tribe)

Circa 1940’s

About the Artist

Willie Seaweed was born in 1873 and died in 1967. His generation was the last to have firsthand experience with the old ways. When Seaweed was a boy, the Kwakiutl families were living in communal houses. Some in his village could remember wearing woven cedar bark and for clothing and blankets and most travel was by canoe. When Willie died, many villages had electricity, families lived in single dwelling frame house, wore clothing much the same as we do today and their transportation was mainly by powerboat or seaplane. His life spanned the decades that had brought his people from their traditional village life to one aware of space exploration, television, ready-made clothing, Christian religion, the Canadian government and alcohol. Each of these had a profound effect on the Indian cultures all along the Northwest coast.

Many of the Indians of Seaweed’s parent’s generation saw more changes in their lifetime than in the 70 years before their parents were born. In 1849, a Royal Charter declared Vancouver Island (Willie’s home) open for settlement. Within 3 years, more than 400 white settlers were given land, former Indian land, by the crown to cultivate and “civilize”. Then gold was discovered on the Island and literally thousands of miners came to the area every month. With the settlers and miners came measles, small pox and tuberculosis. These were deadly diseases for Indian communities, who had no natural immunities to these diseases. Well over one-third of Native American populations were killed in some areas of Vancouver Island.

Some Northwest Indians were also captivated by gold fever. It made them neglect their summer food gathering and the annual salmon run. In the winter of 1858, many Indians starved to death and many more moved to the towns to search for work so they could buy food. When in close contact with the white culture, many Indians fell prey to the vice of liquor. Missionaries also moved into the area during this time and their Christian standards of civilization tried to alter their native cultural heritage. Willie Seaweed’s family was protected from most of these negative influences because their village was extremely isolated.

By the 1870s, the time immediate following Willie’s birth, the Indian population of Vancouver Island was assigned to reservations. Indians had no vote, no representative in Parliament and no rights under the Canadian Constitution, which had declared them unequal because of their race. Many children of Willie Seaweed’s generation attended missionary boarding schools, where they learned to read, write, speak English and adopt European religion and customs. However, Seaweed’s family was very traditional. Willy was raised speaking only Kwakwala (the native Kwakiutl language) and was taught only the traditional skills needed by a Kwakiutl (KWAH-i-tl) man.

During his life, Willie Seaweed worked as a fisherman and an artist. Most artists didn’t support themselves solely from their artwork. People from the neighboring Kwakiutl villages and his own village would commission him to make masks, totem poles and other ceremonial objects.

Although Willie’s father had been a recognized carver, he died before his son’s birth. During traditional times there was said to be only one official carver for a village. To become a carver, a person had to be from a prestigious, high-ranking family. It was a common tradition, also, for the son to continue in his father’s place. Both of Willie’s parents were of royal lineage and he became one of the highest-ranking individuals of this tribal division, the Nakwaktowk. It’s thought that Willie’s artwork developed through an association with his half-brother. Their early masks are quite similar to others created before the turn of the 20th century. The FORMS were simple, quiet and finished in native paints. These colors were obtained from ochre clay (which produced golden yellow or red tones), lime or ground shells (each made white), copper ore (blue/green) and graphite (black). These native paint colors weren’t shiny or bright but they did have a rich depth. About 1920, Seaweed adopted the newly imported “enamel paints” and with this change began to dramatically alter the appearance of his masks. Enamel paints were available in a wide variety of COLORS—bright shiny reds, oranges, yellow, blues, greens, pure white and black. His masks took on a more showy appearance once enamel paints were used.

About the Art

This mask represents a cannibal bird known as the Crooked Beak monster, which appears as part of the cannibal dance, the most powerful supernatural masquerade of the Kwakiutl.

According to myth, the Crooked Beak is one of four monstrous beings who live at the north end of the world and crave human flesh. During the winter season, they come south to the Kwakiutl villages to capture young men of noble families and transform them into cannibals.

The cannibal dance is performed over a period of several days when guests from other villages have assembled for a Potlatch. The Chiefly host stages a reenactment of the myth, with his own son portraying the victim, and fellow clansmen impersonating the dreaded cannibal monsters by wearing frightful masks such as this.

Late in the first evening, after everyone has been assembled and fed in the host’s house, the guests hear strange and eerie whistles, announcing the approach of the cannibal monsters. Suddenly, the chief’s son vanishes, having been kidnapped by the cannibals. In reality, special dance assistants have taken him to the forest where they tell him how to perform the last act of the drama. The last evening of the Potlatch, when the Chief’s son returns to the village, he behaves as if he has become a cannibal himself and he must be restrained from attacking others. He appears to be biting the attendants holding him. The elder men of the village must cure the young man of his cannibal desires. After dancing to cannibal songs, the chief’s son is cured of cannibal influence through ritual acts of the elders. Four cannibal monsters, all monstrous birds with enormous beaks impersonated by men in masks, then emerge from the back of the house and dance around the central fire pit. The Crooked Beak dancers wear the mask tilted upward, stopping occasionally while dancing to hungrily snap the beak.

The Crooked Beak monster is supposed to have a broad, gaping mouth, large red nostrils and a hooked crest above the upper jaw. The graceful spiraling SHAPES above and below the jaws in this picture are unique Willie Seaweed inventions. Seaweed’s exaggerated style of carving shows his creativity and skill, at their best in this picture. The colorful, exciting and dynamic representation of this monster is experienced during the dramatic acting of the danced performance. As a piece of sculpture (it isn’t moving or being worn in this picture) this mask is still exciting, dynamic and dramatic.

Willie Seaweed adopted the use of some non-traditional tools—the straight edge and the compass. Although the Kwakiutl had long made use of stencils to regulate design forms, the addition of the compass and straight edge really gave the art a strong sense of SYMMETTRICAL BALANCE and composition. Seaweed carried this development even further by refining his carving technique so there were no unexpected bumps or bulges. What was meant to be straight was exactly straight and his curves were precisely and gracefully arched. He used the compass to lay out the three concentric circles (circles inside of circles, getting gradually smaller) which formed the eye on his masks. His artwork can be identified by a row of three compass point holes on the eye. This is seen as a kind of Seaweed signature.

Suggested Dialogue

Cedar bark was one of the materials used to decorate this mask.

Can you guess where the artist used the cedar bark?

The mask was made from carved wood, cedar bark and paint. Northwest native artists used the soft, yellowish fiber beneath the rough outer cedar bark to make a type of yarn or thread. To keep from killing the tree, only a small portion of the bark was removed at a time. The yellowish fiber was then dried, shredded and twisted into a type of yarn that could be woven. Capes, skirts, blankets and hats were created by weaving this fiber. Cedar bark fiber repelled rain so it made good protective clothing for the Northwest’s often rainy climate. This dried fiber was also used as fringe to decorate things—such as the Crooked Beak mask seen here. Cedar bark can be seen on the top of the mask and hanging beneath, as if the cannibal bird had hair. Feathers are also attached to the mask .Woven Cedar Bark hats were additionally covered with grease on the outside, for protection from heavy rain.

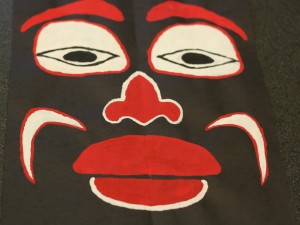

FROG CAPE

Dempsey Bob, Linda Bob, Virginia Bob

About the Artists

The design of this cape was created by a modern day Tlingit (Khling-git) Indian named Dempsey Bob. He was born in 1948 in Telegraph Creek, B.C. (British Columbia). About his art Dempsey says: “I am inspired by the land, our people and our heritage. I inherited a vibrant artistic tradition and have earned the right to be an artist from my people. This land talks to me and I am creative here. I strive to make my art real today, with feelings and power, to show that we have a living culture and art. I want the art to speak to the people today. I continually learn about my culture and myself which helps me in my ongoing quest to develop my artistic style.”

Linda Bob and Virginia Bob sewed the cape. They were also born in Telegraph Creek but now reside in Prince Rupert, British Columbia. Linda stated, “I began making regalia to help keep our traditions alive for my family. Most of the regalia I create is for my family and is worn for our feasts. My grandmother inspired my work with her stories about our people gathering on the shore, dressed in full regalia to greet our visitors.” Virginia said, “When I work on our regalia I am inspired by our ancestors and their stories. My mother and my grandparents told us many stories to pass down our oral tradition and keep our culture alive. I create regalia for our family to express our culture and who we are.”

About the Art

This frog cape is a version of a button blanket. The cape is created with red and black wool. The frog crest is a symbol of the family’s clan. The frogs have been created with red wool and sewn to the black wool. The top red band of the cape has the frontal view of a frog in the center. On the top left side of the cape is a frog head that has been carved from alder wood. The cape is fringed with leather. Above the fringe, in the center of the frog’s eyes, on the backs of the frogs and on the top band you can see white buttons. These button blankets or button capes have white mother of pearl buttons. These capes are worn with masks (regalia) by the campfire to tell stories. The mother of pearl buttons catch the glimmer of the firelight. Today the button blankets or capes are still created for families to wear at family feasts and celebrations.

Suggested Dialogue

CAN YOU FIND ANY OVOID SHAPES? Center eyes for large center frog and frog face along top band, hips of the frogs (or fanny), nose of top band frog face

SPLIT-U SHAPES? Thighs and top shoulders of large center frog

Is there any REPETITION in the cape decoration? There are two smaller frogs that are the same, the round buttons are repeated

Is there any PATTERN? The buttons are sewn on in several REPEATED patterns

Project Idea

- Have kids sew a miniature button cape or blanket using two squares of felt. The bottom piece can be black, navy or dark green. The crest or totem should be cut from red. Small white buttons could be sewn on for eyes. If you have enough buttons, sew on a few more. Fake buttons could be made with a hole punch and a plastic milk jug. Buttons will stay best if they are sewn. Remind kids to be careful. Tacky glue works best gluing felt to felt.

- A button blanket could also be made with paper. The buttons could be cut from white paper and hole punched. Several sizes of white buttons are used on real blankets. A crest or totem shape can be entirely created with buttons used in an outline of the animal shape.

Sun Mask

Kevin Daniel Cranmer

1999

About the Artist

This modern artist, Kevin Daniel Cranmer, is from the Kwakiutl (pronounced KWAH-i-tl) tribe. He was born in Alert Bay, British Columbia and now lives in Victoria. Kevin explained his feelings about carrying on the tradition of ancient Native American artist ancestors when he said, “I started carving at the age of 12. I was inspired by my father . . . [and] encouraged by my mother . . . The greatest satisfaction I have as an artist is creating pieces for my family and seeing them danced with in our ceremonies. When I have the honor of dancing and showing a mask, I feel I embody who we are as a people and where we come from.”

About the Art

The Kwakiutl and Tsimshian (Sim-shee-an) people saw the sky as a beautiful open country where the house of the Sun chief was located. By climbing up a chain of arrows, the traveler could reach it through a hole in the western horizon and could then return to earth by sliding back down on the long rays of the sun. A family’s right to the t’lisala (sun) crest would be explained by their origin myth that would involve an ancestor of the family and the Sun chief.

A face in the center of the sun design, surrounded by rays that may be simple or elaborate, makes this symbol an easy one to recognize. The sun is a popular design of the Kwagiutl, and a large one stands atop the tallest totem pole in the world, at Alert Bay. Kwagiutl sun designs tend to be dramatic, with lengthy and highly decorative rays.

This mask is carved from Red cedar. The center face is the Sun chief. The design on the circle around this face is Raven. The circle is outlined with red rope. The eyes of the center face are inlaid with abalone shell. The abalone shell is also used in the center of Raven’s face, in the center of Raven’s split U-form mouth, on the cheeks and forehead of the Sun chief, on the mouth of the face on Raven’s tail. The abalone shell eyes of the Sun chief are outlined with brass. The other shiny Ovoid shapes in the center and on the rays are also brass. This design is painted using black, white, red and blue. In Northwest Native American artwork, blue isn’t used as often as the other colors are.

Suggested Dialogue

How many ovoids can you find that are made of brass?

Can you find ALL the Split U-Forms on the rays of this Sun Mask? The black tip of the ray is a split U-form, then a brass ovoid, a blue U-form, a black split U-form, a red U-form and 3 more U-forms underneath the red one. (There are 14 split U-forms on all the rays combined—2 on each ray)

Which two types of BALANCE does this mask have? Radial and Symmetrical (formal) BALANCE

Can you find the seven places in this busy design where abalone shell was used as part of the decoration? Near the top in the center of the black point is a circle of shell, just below this, inside a red ovoid is a shell ovoid, shell circles in center of eyes, two shell ovoids on either side of nose, a LINE of shell is used as a mouth in the ovoid painted below the face (it is a second face)

Project Idea

Cut ovoid and U-Shapes from colored paper. Glue to a background in a radial Sun mask design of your own. (Ovoid and U-Form Pattern shapes are included in Project Patterns & Visuals, Packet 9. See your Art Discovery Coordinator.)

Sun Mask (two)

Unknown Artist Bella Coola tribe—Central British Columbia

Carved wood and paint

19th century

The Bella Coola are a Salish-speaking people who once lived in 45 villages located in Canada, along the Bella Coola, Deans and Kimsquit rivers that lead to the Pacific Ocean. It is a rugged and heavily forested area. Once Europeans came to this area, the Bella Coola were struck with numerous deadly epidemics that killed many of their people. Now, the remaining Bella Coola people live in one village, called Bella Coola, at the mouth of the Bella Coola River.

Like their neighbors, the Kwakiutl, the Bella Coola staged elaborate masked rituals during the winter months, to accompany feasts and potlatches. Many of the masquerades dramatized the story of Ahlquntam, the most important of the supernatural creatures recognized by the Bella Coola. Ahlquntam was the creator of all men and animals, the master of fate and the leader of all supernatural beings. He and his counselors decided who would be born among human beings, who would die, and who would be initiated to perform the ritual dances. He was often impersonated at the performances. A dancer wearing a large, humanlike mask would watch the dancers from behind the fire and occasionally pronounce in a powerful voice, “Mortals! See me! I am Ahlquntam!”

About the Art

This mask represents the sun, which Ahlquntam used as his canoe and which he guided across the sky while wearing a cloak lined with salmon. According to the myth, when Ahlquntam reversed his cloak, the rivers would run full of salmon. During the ceremonies the mask was raised against the rear wall of the dance house and traveled across the ceiling to represent the journey of the sun across the sky. This was done with strings and pulleys.

Two ravens, a killer whale and wings (beneath the face) painted on the sun disk frame the three-dimensional face in the center of this carved wooden mask. The face represents Ahlquntam being borne across the sky in his spirit canoe of the sun.

Who was Ahlquntam? The creator of all men and animals, the leader of all supernatural beings, he (and his counselors) decided who would be born and who would die, and who would grow up to perform the ritual dances at potlatches

Look closely at the face. What do you think this supernatural person was like? Do you think he could be friendly at times? What type of MOOD does the mask create?

What would happen when Ahlquntam reversed his salmon lined cloak? The rivers would run full of salmon (a way to explain the annual salmon migrations, when salmon would appear so abundantly in the rivers you could see their backs above the water)

During ceremonies, this mask would be raised against the rear wall of the dance house. As the night wore on, the mask was moved across the ceiling. What did this represent to the Bella Coola people? The journey of the sun across the sky, which Ahlquntam used as his canoe in the sky

The birds and killer whale that surround the face have many Ovoids, U-forms and Split U-forms. Can you find these shapes?

How many COLORS were used to decorate the mask? Red, blue, white and black

(Grade 4-5) Can you find any examples of cross-hatching? (Look for diagonal lines) Inside a teardrop like shape on the body of the killer whale at the top of the mask, on the bodies of the two ravens on either side of Ahlquantam’s face

Project Idea

Draw or paint your idea of what Ahlquntam’s cloak (remember, it was lined with salmon on the inside) looked like from the outside.

Blue Moon

By Klatle-Bhi

1999

About the Artist

Klatle-Bhi was born in 1966, in Vancouver, British Columbia. He still lives there. Here is a quote from this modern day artist, “My ancestral name, Klatle-Bhi, [meaning] ‘Head Killer Whale of a pod of Killer Whales,’ was given to me by my grandmother. The name comes from the Kwakwaka’waw (Kwah-kwah-hooah-kwah) people . . . I carve masks, poles, canoes and work in other mediums such as painting and appliqué (ap-li-kay). My artwork, dancing, singing, canoeing and sweat lodges are sources of purification, learning and my spiritual path.”

About the Art

As well as stealing the sun to bring daylight, Raven stole the moon, along with all the stars that he flung into the sky to lighten the darkness of night.

When there was an eclipse of the moon, the Kwakiutl thought that a codfish, with its great gaping mouth, was trying to swallow the moon. To prevent this from happening, a large bonfire was lit and green tree boughs were added, to create a lot of smoke. As people danced ceremonially around the fire, thick smoke rose up into the sky, making the codfish cough and spit out the moon.

The moon is portrayed much like the sun, with a face filling the center but no rays extend from it. Occasionally the moon may be shown in a crescent form.

Among the Haida, Moon was the exclusive crest of only a few of the highest-ranking chiefs.

Suggested Dialogue

This mask is designed with Operculum shell.

Can you find where the artist used the shell in this mask? For the teeth and spaced around the black outside ring

Besides the shells, where else do you see examples of REPETITION in the mask? The smaller bright blue Split-U shapes around the outside circle, larger dark blue split-U shapes of outside ring, four ovoids (and floating ovoids) in outside ring, red lines in sets of three in outside ring

What COLORS is the mask painted with? Red, white, bright blue, dark blue, black, white (eyes), the main part of the face (background) has been left natural so that the lines of the wood grain show through.

Are there more WARM COLORS or COOL COLORS? Cool

What type of MOOD does the mask create? How does the mask make you feel?

Do you think the shell teeth make the moon face seem more human or less human? (I kind of think the moon looks a little bit as if it he has “buck teeth”—what do you think?)

Does the natural wood color of the mask make the face seem more human or less human? Opinion will vary

Wolf House Posts

Unknown Haida Artist

19th Century

About the Art

The two wolves pictured here are about 7½ feet tall. These “house posts” probably once stood at either end of the inside back wall of a traditional Haida house as symbols of the clan (a group of related families) that lived there.

The Haida inhabited several groups of small, forested islands, off the coast of British Columbia, in Canada. They enjoyed plentiful natural resources and had traditions in common with the Tlingit and other Northwest Coast Native Americans.

The wooden posts were made for a house owner who was wealthy and who would have had the means to afford an expert wood carver. The wood carver might need a year or more to complete the job. When the posts were raised, there would be a great feast—the “potlatch”. Visitors looking at the house posts would know that the families of the house belonged to the clan symbolized by the wolf. The families had a strong connection to the wolf and to its qualities, like quickness and strength. The Haida believed people were related to animal spirits and that at times they could change into their animal totems.

Similar to house posts, totem poles—very tall carvings of many animals and figures, one on top of another, that represented the history and story of a clan—often stood outside at the entrance to a house.

Suggested Dialogue

Can you find a U-Form on either of these wooden wolf posts? There are two individual wolf posts—one is shown from the side view and the other from the front. The top form line of the ear on the side view and the forehead on the front view, the carved shape of the hands

Can you find a Split U-form? Inside the ear and on the nose

Can you tell that each post was once a single wooden log? What helps you to know this?

Show kids approximately how tall 7½ feet would be. Can you imagine these big carved wolves looking at you?

What would you think if you saw them?

What would Haida visitors coming into the house in which they were placed think? The people who lived in the house were from the wolf clan and the wolf was their totem

If a friend came to your house, how would he or she know that it was your house?

What things in it show that this is your house? Is this the same in any way?

Project Idea

- Create a Wolf House Post with clay.

A week beforehand, create plaster “logs” for kids to carve their Wolf House Posts. Use paper towel tubes, blocked at one end with either waxed paper or aluminum foil held on with rubber bands. In a large container, thoroughly mix 1 part Plaster of Paris and 1½ parts vermiculite (found in garden stores—fairly inexpensive). Pour into tubes and set aside to harden for 5-7 days. Peel cardboard tube from plaster. Draw simple designs for the post on paper, then transfer the sketch to the block with pencil. Don’t forget to use ovoid and u-form shapes in the design, to make it authentic. Remind kids to KEEP THE DESIGN SIMPLE! Begin carving with the largest shape. Use plastic knives, toothpicks, and metal spoons to carve. When carving is complete, sand with medium sandpaper. Wipe with a damp paper towel and paint. The finished posts are lightweight.

Crest Hat

Unknown Tlingit Artist

19th Century

14” high

About the Artist

An unknown Tlingit (pronounced KHLING–git) artist created this hat sometime during the 1800’s. Crest Hats were made for important feasts. This Bear Crest hat belongs to a Bear clan in the Tlingit tribe. A clan is a group of related families within the tribe. It was a treasured possession to be worn by the various family heads and was thought of as a crown, symbolizing the spirit of the brown bear. The brown bear, like the one on the hat, was an important animal to the Tlingit.

The mask is made from carved wood. The center of the eyes and ears and the teeth are abalone shell. The tongue is made of copper and it moves. Abalone shell and copper were considered valuable to the Tlingit.

The hat was usually displayed at “potlatches,” feasts celebrating a birth, a special moment in the life of a family member or marking a death. A potlatch included the giving of many valuable gifts and dancing, music and storytelling. The number of rings on a crest hat is said to mean the number of potlatches at which the hat was worn. This hat has eight rings.

Suggested Dialogue

The artist added a realistic touch to this mask—fur. Can you see the bear’s fur? Fur is glued into drilled holes along the edges of the ear. The fur is human hair.

How many potlatches has this hat been worn to? It has 8 rings—8 potlatches

Do you wear hats? What kinds of hats do you wear?

Does this look like a hat you’ve ever seen?

Would you like to wear this hat? Why or why not?

How would you feel wearing this hat?

Do you think the artist tried to make the hat look like a real bear or an imaginary one?

In what ways did the artist make it look real or make-believe?

How many different colors do you see in this hat?

How big do you think it is? 14” high

How heavy do you think it would be?

What is your favorite part of the hat?

Project Idea

- Create a clan hat using a tag board or poster board base.