All of the pictures in this packet are painted in a Folk Art style. The pictures are very simple. Folk art, or Naive art, is artwork created by an untrained, unprofessional artist. There is only one true folk artist in this packet—Horace Pippin. Palmer Hayden, William H. Johnson and Jacob Lawrence were all professionally trained artists who chose to paint in a simple folk art style. They felt this simple style of painting brought out the simple, down to earth lifestyle of many people of their African-American culture. Although they were able to paint in a much more realistic way, the simple style they chose communicated a specific feeling or MOOD to the viewer.

The major technique used to give these pictures depth or perspective is RELATIVE SIZE—things closer to the viewer are larger than the things in the background. This is one of the simplest ways to create perspective in a picture. Notice how the janitor is much larger than the mother and her child. The women at the table, in The Domino Players, are larger than the woman in the rocking chair, who is farther away. The people in the wagon are much larger than the buildings on the hillside in Going to Church.

The Domino Players has many varied PATTERNS. Point out the PATTERN of the clothing, the LINES of the floor boards and the quilt. Compare the PATTERN of the floor boards with The Janitor Who Paints. Ask the kids if they can find PATTERN in the picture Going to Church. The PATTERN of this painting is in the repeated LINES representing plowed fields and fences.

Be sure ALL 4 pictures are returned to the Packet Carrier after your Presentation is finished.

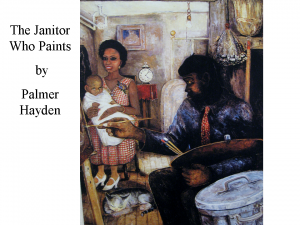

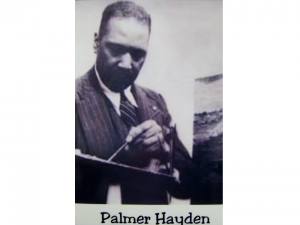

The Janitor Who Paints

By Palmer Hayden

About the Artist

Palmer Hayden was born as Peyton Cole Hedgeman, in 1890, in Wide Water, Virginia. When he enlisted in the army, his commanding Sergeant could not pronounce Peyton’s real name so his sergeant called him “Palmer Hayden” instead. Peyton kept the name, Palmer Hayden, for the rest of his life.

As a child, Palmer had shown some talent for making pictures so, as a young man in the military, he enrolled in a correspondence course in drawing. This was his first formal art training. Palmer Hayden is often referred to as a self-trained artist, yet he received formal art training in New York, the Boothbay Art Colony in Maine, and in Paris, which was the art capital of the world in Palmer’s day. Palmer lived in Paris from 1927 to 1932. Palmer just chose to paint in a style that looks self-taught.

Palmer lived until 1973.

About the Art

Although this painting is not a self-portrait, the scene shown here was familiar to Palmer Hayden. Like many other artists, Palmer experienced hard times and took odd jobs to support himself. Since Hayden was referred to as “a working man who also painted,” he most likely had great respect for the man, a personal friend of his, featured in this painting. The man’s name was Cloyd Boykin. Palmer once said of this painting, “I painted it [this portrait] because no one called Boykin the artist. They called him the janitor”.

The alarm clock, in the background of the painting, is a constant reminder of the lack of time the working man has for his artistry. The clock takes up an important place in the picture. It could be a reminder that the janitor can only paint before or after work.

This janitor lives in a very small apartment but although the room is crowded, it is neat and clean. You can see the apartment’s water pipes in the upper left corner of the painting and the light bulb is exposed, with no fixture or shade. These things remind us that the janitor is not a well-to-do man. The things around the janitor are placed uncomfortably close to each other. Hayden exaggerates this effect by placing the artist, his easel and a trash can in the front (FOREGROUND) of the picture.

What kinds of tools can you find in this picture? We can see the tools a janitor uses—trash can, broom and a feather duster. We also see the tools an artist uses—easel, paint palette, paint brushes. These things are clues to the viewer of this painting. They surround this janitor and artist.

The job of janitor is usually dirty, so a person who does this job wears casual clothes to work. An artist usually wears something they will not mind spilling paint on. What is the janitor wearing in this picture? Why do you think he is dressed so formally?

The woman posing with her baby is wearing a corsage on her dress, high heels and earrings. She gives us the idea that she wants to look her best for the painting the janitor is creating.

Project Ideas

- Draw or paint a picture of an artist who also has another job. What about a fireman who paints or a policeman who paints? Other ideas of jobs could be a doctor, lawyer, musician, ballerina, auto mechanic, dog-catcher, veterinarian, baseball player, football player, airline pilot, truck driver, taxi driver, bus driver, tug-boat captain, farmer, zookeeper, teacher, garbage man, secretary, soldier, waitress, cook, or maid. Be sure to include at least three tools this person would use for their regular job and at least three tools for their artist job.

- Have a contest to see who can come up with the most interesting and creative picture of an artist doing two jobs (one of them painting or sculpting) at the same time!

- Create a cardboard paint palette and bring in five additional tools to pose as a “Mom/Dad Who Paints”.

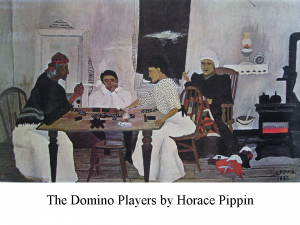

The Domino Players

By Horace Pippin

About the Artist

Horace Pippin was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, in 1888. When he was 7, he and his mother moved to Goshen, New York. Horace said that at the age of 7 he began making pictures. He won a set of crayons in a magazine art contest. Horace bought a large piece of muslin (fabric). He cut the material into small squares, fringed the edges and made decorative doilies.

At 14, Horace worked doing odd jobs on a farm. A year later he began unloading coal for a living. Pippin also worked as a mover, an ironworker, a hotel porter and a junk dealer. In 1917, Horace enlisted in the Army and was sent to France, during World War I. Horace entered the 369th Regiment, the first unit of African-American soldiers to go overseas. Pippin recorded his terrible experiences in the war by keeping a journal that he wrote and drew in.

Horace was badly wounded during the war. A steel plate was inserted in his right shoulder and remained there for the rest of his life. His right arm became shriveled and for eleven years after the war he couldn’t draw. One day Horace noticed a poker next to a potbellied stove. He found a piece of wood, and supporting his weak right hand with his left, he began to burn a picture into the wood using the poker. It took an entire year for him to finish the burnt wood picture but once again Pippin was an artist. This exciting new discovery gave Horace the courage to try his first real oil painting, in 1930. Horace named this first oil painting End of the War: Starting Home.

When Horace returned from the war, he settled in West Chester Pennsylvania. Here he painted until his death, in 1946. His injury made his painting arm very weak and Horace had to push his right hand along with his left hand, in order to paint. Horace painted his painful memories of the war. It was his way of healing his spirit, which had also been wounded by the war. Horace also painted good memories of his childhood. He once said, “Pictures just come to my mind and then I tell my heart to go ahead.”

Horace’s painting studio was a small front room that was so poorly lit he was forced to constantly use a naked 200 watt bulb in the room’s only light fixture (like the one in Palmer Hayden’s The Janitor Who Paints). Horace often painted for 17 hours at a time, supporting his injured right arm with his left hand and using tiny brushes. Someone who recognized his unique ability eventually discovered Pippin’s paintings. Horace’s first exhibit was at the West Chester Community Center, in 1937.

In 1940, Pippin attended classes at the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania. This was the only formal art education that Horace Pippin ever received. Although he learned a few art and painting basics at the Barnes Foundation, Horace was entirely self-taught. He did not believe that anyone could really instruct a person in art because you just had to do that yourself. Because he was a self-taught artist, Horace Pippin was considered a PRIMITIVE PAINTER. He was the first self-taught African-American artist to gain recognition for his paintings and these paintings are still being exhibited in major museums throughout the United States and the rest of the world.

About the Art

Pippin loved to paint the simple things he knew best—interior scenes showing the tenderness of family members towards one another, people working together on a farm, and Still Life arrangements.

In this painting, we see three women and a boy sitting in a room. There are patches on the wall where the plaster has chipped. Two of the women are playing dominos with the boy at the table.

What do you notice about the boy’s frame of mind? He looks tired, as if he is not really paying attention to what is going on around him.

What is the woman in the rocking chair doing? She is sewing on a quilt. We can see fabric scraps and a pair of scissors on the floor, next to her.

What time of day is it? The clock says 8:00. It is probably evening because there is usually more time to relax and play a game at that time of day. If it were 8:00 in the morning, they would probably be cleaning up breakfast dishes or getting out the door to work or school.

What type of MOOD do you see in this picture? Calm, quiet, warm and cozy

Can you find PATTERN in this painting? The strips of COLOR on the quilt, the black dots on the woman’s shirt, the red bandanna on the other woman

These are probably hard working people. The room and their clothes seem plain, clues that they do not have much money.

Project Ideas

- Set up a small table, with a board game laid out, at the front of the room. The more colorful the game board the better. Ask three students to come up and play the game (or pretend to play the game) while the rest of the class draws them. After a few minutes, let the first three sit and ask three more to come up and play the game. This gives everyone a chance to draw as well as several chances to be a participant in the scene. Explain that the scene they are drawing will be a PRIMITIVE PAINTING, so there is no pressure to make their pictures look like an exact photograph of the scene. Instruct them to draw only the main SHAPES of the scene—the table, people sitting and the game. The details will be added as they paint their basic shape outline of the scene. Stress the importance of creating PATTERN in the scene. Even if the players have no PATTERN on their clothes (dots, stripes, plaids, etc.) encourage the class to add these to their picture as they are painting. After only about 15 minutes of drawing the basic outlines of the scene, have everyone sit and begin painting. Unfinished details in their drawings can be filled with their imaginations as they paint.

- Bring in a set of dominoes to show younger classes (K-1). Design a creative design PATTERN with the dominoes, on a table at the front of the room. Discuss the number of dots found on each domino in the arrangement and stress the importance of paying attention to where each is placed in the design. Have kids cut the same number of black rectangles and arrange the rectangles on a background in the same arrangement as the one you created for them. Use a hole punch on white paper and cut a small sandwich bag of white dots to pass out in the class. Kids will arrange the dots in the same way that they are arranged on the dominoes that you have used in your display at the front of the room. This is a great geometric SHAPE project for K-1 classes.

- Have the kids design a game board and game pieces for their own game. Kids will need to write out the rules for their game first. The board design could be drawn on a large piece of tag board, white construction paper or an open file folder. Draw a pattern of squares and color with felt pens or heavy crayon. Show class how to make a line of squares by tracing both sides of a ruler and dividing it into equal sections. You might buy small, inexpensive wooden blocks kids could paint for a game dice. Dots can be painted with a toothpick dipped in paint.

- Instead of an art project after your presentation, bring in some board games for the kids play these instead. With all the modern video games these days, many kids have never played simple games before. Check with the teacher ahead of time for this. See if any of the other parents in the class have a domino game. You might send home a handout ahead of time, to see if parents could find and send in some of these games to use on the day of your presentation. If you can find enough domino games (1 for every 4 kids) you could teach the class how to play the game. Checkers is another nice, old-fashioned game to play. Maybe you could find enough for a combination domino/checker game activity.

- Cut small pieces of muslin fabric for each student (approx. 8” squares). Help the class fringe the edges of their square or fringe the edges ahead of time for them. Have them use crayons to create decorative doilies, like Horace Pippin did after he won the art contest. The designs could be ironed into the fabric to make them permanent (cover crayon design with paper before ironing).

- Point out the woman in the rocking chair, behind the domino players. Discuss what she is doing (sewing a quilt). Create a quilt square from colored paper, wrapping paper and/or wallpaper shapes. (See Pattern pages) Display as a class quilt by combining the squares together on a bulletin board.

- Use a quilt pattern page and paint or color fabric PATTERNS on it. Cut out the finished square and mount on contrasting black construction paper.

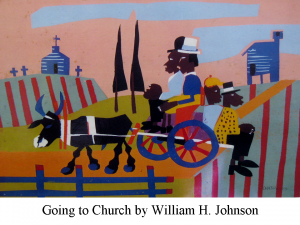

Going to Church

By William H. Johnson

(Circa 1932)

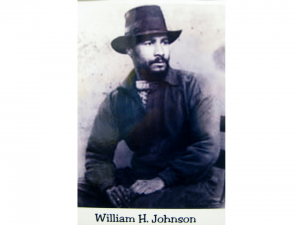

About the Artist

William Henry Johnson was born March 18, 1901, in rural Florence, South Carolina. Because he was the oldest child in the family, William had to work odd jobs while he was in school, to support his mother and four younger siblings. He missed a lot of school because he had to earn money to feed the family.

William moved to New York City from Florence, in 1918, at the age of 17, to pursue a career as a newspaper cartoonist. He settled in New York at the dawn of the Harlem Renaissance, a period of literary and artistic activity among blacks, that was centered in New York City’s Harlem. At that time, Harlem was the center of African-American music, dance and art. The Harlem Renaissance lasted for about 10 years, before the stock market crash of 1929 marked its end. Johnson became an important part of this movement.

By 1921, Johnson was admitted to New York’s National Academy of Design. At the Academy, Professor Charles W. Hawthorne guided the talented young man and provided him with employment to fund his studies. Johnson also worked in an artist’s studio in exchange for painting lessons. His talent was recognized as having tremendous potential and William was encouraged to study art in Europe, so he sailed to Paris in 1926.

After nearly two years in France, William returned to America and to his childhood home in Florence, South Carolina. Using his friends and family as subjects, Johnson started painting the everyday activities of the people in Florence.

William returned to France and married. The couple moved to Denmark. Johnson painted many landscapes while he lived there. He experienced less prejudice than he had in the United States and his work was taken more seriously. Johnson and his wife, who was also an artist, traveled and lived all over Europe. In 1938, William and his wife moved back to America because of the threat of the Nazis and another World War. They settled in New York and he was again able to “paint his own people”.

Johnson got a teaching job at the Harlem Community Arts Center, through the government sponsored Works Progress Administration (WPA) program. The paintings that Johnson then began producing concentrated on African-American subjects and they were painted in a style that looked like American Folk Art, or the work of an untrained, Primitive painter. Johnson was actually a professional artist who had been schooled in the techniques of fine art. He just chose to paint in this primitive style for his paintings, which told the story of his heritage and his background. Going to Church is painted in this primitive type style.

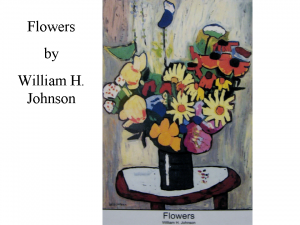

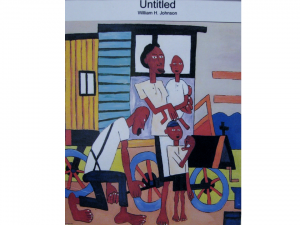

About the Art

Johnson has painted this picture using simple SHAPE, COLOR and LINE, with few details. It is interesting that he went to the trouble to add the details of their fingernails, white dabs of color against dark brown skin. The two trees are just triangle tops with brown LINE underneath. The buildings are SHAPES with a few simple LINES. The fence, in the FOREGROUND, is a few LINES of color. The road the family is riding on is an angled SHAPE of COLOR.

This is a Sunday morning country scene, with a farm family, wearing their best Sunday clothes, taking the only form of transportation they can afford, to the church on the hillside, in the distance.

Suggested Dialogue

The distant hillside and other landscaping have rows of painted LINE. What are these lines? The plowed rows of vegetation on the farms in Johnson’s rural Florence, South Carolina.

What animal is pulling the wagon? A cow because the family is too poor to afford a horse.

Notice the unusual way the artist painted the sky. Have you ever seen the sun in the early morning?

Sometimes it has a lot of pink, as the sun rises over the horizon and is reflected against the clouds. Johnson tried to show this.

Project Idea

Johnson’s painting is a SERIGRAPH, or silk-screen painting. Paint a background, with solid colors of tempera paint, that has a foreground, middle ground and background similar to William H. Johnson’s painting. Create the same type of “stamped” look for the details in your background with homemade stamps and tempera paint. The stamps should be Geometric SHAPES (square, rectangle, circle, and triangle) and short, medium or long LINES. Use the shapes and lines to stamp buildings, streets, trees, fences, plowed fields (like the one in Johnson’s painting) in the background. Leave an area in the center of the picture blank. This will be where the center of interest, or the main character or characters of the picture will be painted. Once the background is dry, lightly outline with pencil (in the center area) people or a person doing something that fits the background you have created. Paint your finished drawing with tempera paint.

- Suggestions for middle ground picture subject:

◊ Kids riding bikes

◊ Lone person riding bike

◊ People playing baseball

◊ Kid delivering newspapers

◊ Kids bouncing a ball

◊ People playing basketball

◊ Girls jumping rope

◊ Girls playing hopscotch

◊ Someone riding a horse

◊ Family riding down the road

(in a car or a horse drawn wagon)

◊ Family on a picnic

◊ Family going to church

◊ Farmer plowing a field

◊ Scarecrow standing in a field

◊ Kids with a lemonade stand

◊ Small child pulling a wagon

◊ Mother pushing a stroller

◊ Person walking a dog

◊ Person mowing a lawn

◊ Mailman delivering mail

◊ Neighborhood ice cream truck

◊ Person riding motorcycle

◊ Parade down Main street

- You may want to create the stamps ahead of time, so the class can use them for this project. It will take several hours for most of these stamps to dry before they can be used. An alternate idea would be to use one class for kids to create the stamps and come back to have the class use their stamps for painting this suggested picture. (It’s nice to do at least one bigger project a year, which takes two class periods to finish.) Here are some suggestions for making the stamps used in creating the background:

◊ Cut corrugated cardboard into the shapes needed. Glue these shapes to a larger square of cardboard and attach a construction paper handle to the back of the stamp. This makes it easier to press and lift the stamp. To paint with these stamps, paint the bottom shape with a paintbrush, being careful not to get any paint on the cardboard background. When changing colors, wipe the stamp with a paper towel. The paint needs to be removed right away or the stamps will quickly become too soggy to use.

◊ Cut stamp shapes from foam meat trays (instead of corrugated cardboard) and follow the steps above.

◊ Rubber inner tubes can be cut into stamps. These can be used again (for a future project) but YOU will have to make these at home, because the rubber needs to be glued with rubber cement. (Kids cannot use this in the classroom anymore.) You will need to stack these thinner shapes in two layers. Use rubber cement to glue two pieces of inner tube together. Draw shapes with a ballpoint pen and cut out with scissors. Glue shapes to cardboard or small scraps of wood to make a more permanent stamp.

◊ Buy foam craft sheets with a peel off sticky back. These can easily be mounted on small squares of corrugated cardboard or wood. This material makes the best and most permanent stamps but it is a little more costly.

(Creating rubber stamps can be a great lesson in LINE, ORGANIC SHAPE, FREE-FORM SHAPE and/or GEOMETRIC SHAPE for younger classes and will be a good project for almost any packet topic.)

Untitled

William H. Johnson

Flowers

William H. Johnson

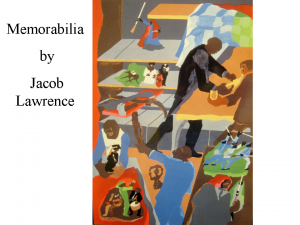

Memorabilia

By Jacob Lawrence

Color lithograph

31¼” x 22½”

“I paint the things I have experienced … I paint the American scene.” Jacob Lawrence, 1995

About the Artist

When he was thirteen, Jacob Lawrence moved to Harlem, in New York City, with his mother and siblings. There he was enrolled in an after-school program at the Utopia Children’s House, as Lawrence later writes, “…to keep me busy while she [his mother] was at work.” It was there that Lawrence met Charles Alston, an African-American artist who encouraged Lawrence’s interest in art. Alston taught the after-school art program that Jacob was enrolled in. (*See Packet 18. Abstract Art for information about Charles Alston.)

While Lawrence was still at Utopia Children’s House he learned about General Toussaint L’Ouverture, a black slave who led a revolt that created the first black republic in the Western Hemisphere, Haiti. This was the first time Lawrence heard about African-American heroes (a subject lacking at his public school) and it had an overwhelming effect on the young boy. A few years later, in 1936, Lawrence painted a series based on the General’s life titled Toussaint L’Ouverture. He would go on to portray other famous African Americans including Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass.

When Alston began to teach at the Harlem Art Workshop, Lawrence followed his teacher. By this time, Harlem had become a magnet, attracting dozens of African-American intellectuals, writers, artists, and musicians who had discovered and were expressing their shared heritage in their work. The resulting artistic and literary expression became known as The Harlem Renaissance. Encouraged by his friends and teachers, Lawrence began to learn how his own experiences fit into the larger African-American story in the United States. Lawrence participated in discussions, attended lectures and spent hours at the library reading books about the African-American experience.

One of the most significant works of art that Lawrence created at this time is The Migration Series (1940-41). In sixty paintings Lawrence explored the social dynamics of the Great Migration, so called because between the years 1915-1945 thousands of African Americans migrated from the South to the North, searching for a better life. The power of this work brought Lawrence his first major sale and wide acclaim and recognition.

In the decades following, Lawrence traveled, taught, and continued to paint. His awareness of the African-American heritage and the awakening consciousness of the nation towards injustices to African Americans led Lawrence to embrace and portray the new African-American protest movement led by the reverend Martin Luther King Jr. “Some people may hate me for holding up a mirror,” Lawrence said, “but I can’t drop it.”

Lawrence was at heart a teacher and was often in demand as a guest instructor in communities and universities around the nation. He also visited public schools to talk about his work and the African-American experience to school children. His many children’s books, including The Great Migration and Harriet and the Promised Land, celebrated the shared heritage of African-Americans.

Lawrence moved to Seattle in 1971 and for the next twelve years taught at the University of Washington as a full professor. One of the more significant series completed at this time, The Builders, was inspired by the rapid growth of Seattle during the decade of the 1970’s. For Lawrence, the act of building, whether it be structures, careers, relationships or compassion and understanding between people, is a positive human endeavor full of hope and promise. After his retirement from the University of Washington, Lawrence continued to paint, accepting commissions and short-term teaching engagements until his death, in May of 2000.

About the Art

In 1988, Vassar College, in New York, commissioned Jacob Lawrence to create a work celebrating two decades of its Africana Studies Program. Memorabilia summarizes the recurring themes of Lawrence’s work: the American story. The setting is a storeroom in a museum where conservators are working. Around them can be found a length of adire cloth and carvings from Africa, figurines depicting African Americans including Harriet Tubman, three black Union Soldiers from the Civil War, jazz musicians, preachers, gospel singers, and a little graduate. The collection of tools on the lower shelf represents the collective labor of African-Americans, their shared heritage, and the building of the African-American community in the 20th century. These images represent ideas worth keeping, guarding, and treasuring with the same care a museum shows for any object in its collections. The tools also suggest the idea of building, prevalent in Lawrence’s work at the time.

Suggested Dialogue

Look for LINES. Can you see LINES? Are they diagonal, vertical, horizontal? Most of the LINES are horizontal and diagonal. The shelves have horizontal and diagonal LINE. The corner that the shelves butt up against is a vertical LINE. The tables in the front of the painting have diagonal LINE.

Can someone point out the LINES to me? Why are the LINES important? Most of the lines divide the picture into separate areas.

What would happen if you took some LINES out of the picture?

How many COLORS are there in this picture? What are the COLORS? RED, WHITE, BLUE (various tints and shades), GREEN (various tints and shades, BROWN (various tints and shades) and basic BLACK.

Which COLORS are repeated in the picture? Show me where COLOR is repeated. How does the repetition of these COLORS move our eyes through the picture? The red moves our eyes around the picture from side to side and top to bottom. The green starts at the top right and zig-zags lower to the left, then lower to the right, and finally to the lower left—to move our eyes from the top to the bottom of the picture. The tan begins on the shelf near the top center of the picture, repeats on the shelf fronts below on the left, repeats again on the table to the right and the floor in the bottom center. Black repeats back and forth and from top to the bottom of the picture. Tints and Shades of brown are also repeated throughout the picture.

What would happen if you changed a COLOR? What if you removed one of the colors?

Most of the COLOR of this painting is flat and evenly painted. The artist didn’t carefully blend highlights and shading into the color to help it appear realistic, like a photograph. The painting has a “folk art” appearance, as if the artist had no formal art training. (Jacob Lawrence was a trained and educated artist who was also a full professor for twelve years at the University of Washington, in Seattle.)

What kinds of things (memorabilia) found in this picture are important to African-American heritage? What does each of these things represent? Some items represented on the shelves and table include Harriet Tubman—the black woman who freed many black slaves on the Underground Railroad, a horse racing jockey, a minister, a choir singer, a hammer, Union Civil War soldiers, jazz musicians, and a graduate.

Project Idea

- Send home a paper, the week before your presentation, requesting that students bring in some objects that represent their family or cultural heritage and items of importance to their life (grandparents picture, family portrait, parent’s wedding picture, soldier’s portrait of grandpa, brother or dad, baby blanket or baby clothing child once wore, special baby toy, an ancestor’s journal, various items from a country or countries the family immigrated from, sports trophy child has earned, favorite books, favorite game, etc.). You should also bring in a few extra objects representing general American Heritage objects (flag, picture of George Washington, Statue of Liberty, baseball glove, football, basketball, apple pie), in case some kids forget to bring their objects in. The kids will paint a collection of objects that have meaning in their life and heritage.

Have kids first create a thumbnail sketch to plan their painting. Use tempera paint in only red, white, blue, green, brown and black—the same colors Jacob Lawrence used in his painting. Kids can create shades and tints of these colors (by adding black or white) if more colors are desired, like Jacob Lawrence. Encourage the class to try to move their color throughout the work as Jacob Lawrence did (be sure to discuss this beforehand) to help the viewer’s eyes move through the picture.

Consider having grades 4-5 write a page that explains the significance of the objects they chose for their painting. What do these things represent to them? What do these objects tell others about themselves? Which objects represent things about their family heritage and which objects represent things unique to themselves?

Jacob Lawrence with one of the old tools (a planer) from his

extensive tool collection.

Jacob Lawrence in his studio (1994)

Historical Reference

The Great Migration: Following World War I, African-Americans facing extreme poverty and a horrific disregard to their rights in the South (Jim Crow laws, lynchings and terrorism of the Ku Klux Klan) began heading North, to the Mid-Atlantic, Northeast and Midwest by the thousands. Although they hoped for a better life, they often found racism and unemployment, especially during the Great Depression. While life was not as rosy as had been hopes, African-American children could attend school and their parents were allowed to vote. The most significant outcome of this migration was that African-Americans, from different parts of the nation, were coming together and telling their stories. In the process, they found a common heritage, filled, not only with grief, but triumphs as well. This, paired with their newfound freedoms, helped to raise the hopes, aspirations and consciousness of African-Americans.

Harlem Renaissance: Following World War I, dozens of talented African-American intellectuals, writers, artists and musicians were drawn to Harlem, a predominantly African-American neighborhood, in New York City. Among them were intellectuals W. E. B. Dubois and Alain Lock; writers Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, and Countee Cullen; artists Charles Alston, Romare Bearden, Aaron Douglas and Augusta Savage; as well as performers Louis Armstrong, Josephine baker, duke Ellington and Paul Robeson. They, and others, expressed their African-American heritage through their work. The resulting artistic and literary expression became known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Civil Rights Movement: The movement began to gather strength following a series of events (such as brown vs. Board of Education, Topeka, Kansas or Rosa Park’s stand in Montgomery, Alabama) in the 1950’s and gained momentum with the nonviolent action led by the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., throughout the 1960’s.