1. The Episode of the Buffalo Hunt

2. The Scout: Friends or Enemies?

3. The Old Stagecoach of the Plains

Packet Extra:

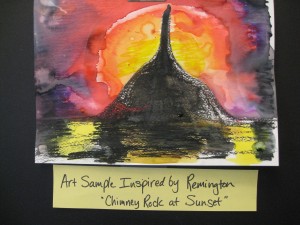

Sample Projects:

Western art is one of the few “schools” of art that is defined by a selection of subject matter rather than a technique. Western art had a specific purpose—to record and comment on the events, inhabitants, and characteristics of America’s Western states.

Much of the work of the earlier arts of the West was financed and encouraged by the United States government and American business. For example, Seth Eastman was an official illustrator for the Department of Indian Affairs in Washington. Other Western artists, such as Catlin, Bierstadt, and Moran, accompanied official exploring expeditions. Their illustrations of the new frontier played an important role in the course of American history. Not only did these works encourage settlers to move out West; Moran’s representation of what is now Yellowstone encouraged Congress to create the national parks system.

After the Civil War, the new mass media, particularly magazines, began to hire artists to create dramatic illustrations for their editions. Several careers were started and maintained by Harper’s Weekly alone, and Scribner’s and Outing magazines were not far behind in this type of sponsorship.

Western art helped draw people from the East to the lands of the American West. The negative side of this was that the purity and splendor of the West was invaded with technology, engineering and the worst of the Eastern American civilization. By encouraging settlement, Western art had also encouraged wars that resulted in the decimation of the Indians it had so highly praised and the end of the unfenced openness unique to the American plains. This wonderful form of art, so fresh and alive, had encouraged the end of an entire way of life, exactly what it had not wanted to happen.

No other name more automatically comes to mind in the category of Western Art, than that of Frederic Remington. The work of this artist, illustrator and sculptor was well known in all levels of the American society of his day. He remains one of America’s best-known and best-loved painters.

This is an excellent packet for discussing MOVEMENT. Remington’s keen observation skills observed that horses raised all four legs while running before it was even proven with a camera. Even as a child, Frederic’s sketches and paintings were filled with action and movement. Concentrate on the exciting stories Remington tells in his paintings. Throw in a few exciting historic facts. Cowboys and Indians are still fun!

Make sure ALL 7 pictures are returned to the Packet Carrier after your Presentation is finished.

Frederic Remington—Cowboy Artist

Artist Frederic Remington was born in Canton, New York, on October 4, 1861. His parents were Clara Sackrider and Seth “Pierre” Remington. Remington’s father, Pierre, was an active person. In 1856, he and a local lawyer founded a newspaper, the St. Lawrence Plaindealer. But soon after the birth of his son, Pierre Remington left the paper and volunteered for service in the Union army, during the Civil War, where he bravely fought for the North.

Pierre Remington retired from military service with the rank of major. When he returned home from the Civil War, he brought exciting stories of his military adventure and vivid descriptions of the land to the west of New York—“The Wild West”. Frederic’s father enjoyed shared exciting stories at the dinner table. Young Frederic loved listening to his hero father’s thrilling and exciting exploits. His father’s stories planted an interest in Frederic to see Western America himself someday.

Young Frederic was an athlete and spent much of his time swimming, fishing and riding horses. Canoeing was another one of his favorite activities. Frederic also spent a lot of time drawing pictures. His favorite things to draw were horses, soldiers and Indians. When he was eight, he painted two watercolor scenes from the Civil War. Both were inspired by his father’s adventurous storytelling. The paintings demonstrated that, even as a boy of eight, young Frederic had a clear sense of detail and an unusual ability to create the illusion of movement in his artwork.

Remington’s first “art studio” was his uncle’s empty stable. Sometimes he would borrow the neighbor’s horses and study and sketch them here. He worked hard to show every detail in a very realistic way and also tried to capture the subjects he drew in poses of action and movement.

In 1872, the Remington family moved from Canton to Ogdensburg, New York. This larger town was twenty miles northwest of Canton, on the banks of the St. Lawrence River. Remington’s father sold the Plaindealer and began editing the Ogdensburg Journal. Ogdensburg was more of a city than Canton had been. The population was more than 10,000 people, and the town was an important commercial port, serving as a final stop for large transatlantic ships.

During the years in Ogdensburg, Frederic continued to sketch and paint his favorite subjects and his artistic skills grew. Pierre Remington was proud of his son’s drawings and paintings; although he hoped Frederic would someday follow in his own footsteps and become a journalist. In Ogdensburg, Fred created his first oil painting, a small portrait of an army officer.

In 1876, Frederic’s parents sent him to Highland Military Academy, in Massachusetts. His father believed that military training would build character and teach Frederic the importance of discipline and effort. After spending two years at the academy, Remington had to choose which college to attend. He was tempted to go to Cornell University and study journalism, a choice his father would have liked. Instead, Frederic chose to follow his interest in art and enrolled in the School of Fine Arts at Yale University, in 1878.

Remington learned the basic principles of art at Yale. Part of his studies required him to draw from plaster models of ancient Greek statues. (This had been a traditional way of training serious artists for hundreds of years.) He lost patience with these exercises because he preferred drawing subjects that moved and were very much alive. The plaster models were lifeless and boring to Frederic.

Remington enjoyed and thrived on athletics at Yale. He was a successful heavyweight boxer and football player. The sportsman and the artist came together when Frederic’s first published illustration appeared as a cartoon feature in the Yale Courant. It showed a slapstick drawing of an injured football player (Remington himself) humorously recuperating from a whole list of game injuries.

Frederic decided to quit Yale after the football season of 1879. His art classes did not appeal to him anymore, money was low, and his father was very ill. Pierre Remington died a short time later, in February of 1880.

In March of 1881, Frederic finally took a trip west, to the place he had dreamed about and drawn pictures of since he was a boy. His travels took him through the Dakotas, Texas, Arizona, the Indian Territory, and eventually to Montana. He rode cowponies, roped cattle and faced the day to day difficulty of survival in the Old West.

Remington had an experience in Montana that settled what he was going to do for the rest of his life. Here he met an old wagon driver. One evening, while the old man shared his bacon and coffee with young Remington, the driver told about how he had seen the western frontier growing smaller and smaller through the years. He said, “…now there is no more West.” Later, Frederic Remington recalled his thoughts at that moment with the old man. This is what he had to say:

“I knew the railroad was coming—I saw men already swarming into the land…I knew the wild riders and the vacant land were about to vanish forever…Without knowing exactly how to do it, I began to try to record some facts around me [by drawing and painting scenes of the “Old West”], and the more I looked the more the panorama [view] unfolded.”

Inspired by the words of the wagon driver, Frederic Remington now had a purpose in his life—to record life in the Old West for future generations before it vanished. The fact so many of the images Remington painted are still familiar to us today, demonstrates that the artist was successful in this effort.

As a truly “American” painter, sculptor, and illustrator, Frederic Remington was the most famous artist of the American “Wild West”. His art combines REALISM with storytelling. He gave us an objective view of America’s western frontier and recorded the growth of this frontier with an ever-increasing talent. He understood this country, its ruggedness, and its beauty. He understood the relationship of the cowboy to his horse, and intimately appreciated the saddle he rode in. Remington’s paintings and sculptures, in exciting and realistic detail, shared the original American western way of life, which had already begun disappearing as he first traveled west, at the young age of nineteen.

Project Ideas

- Create a Bison from torn paper. Use a small piece of brown fur to cover his forelegs, shoulders and head.

- Sculpt a bison with clay. Use a toothpick to create sunken relief TEXTURE (fur) using line.

- Paint or draw a scene showing MOVEMENT and action. Volunteers might have kids brainstorm a few ideas for action scenes such as swinging in a swing, jump roping, skipping, throwing a ball, wind blowing through trees, rocks falling over a cliff, skipping a rock across water, a race, etc. Discuss additional ways to show action—grass, bushes, or trees leaning to one side can create the appearance of wind, the pose of the arms and/or legs, hair flowing in the opposite direction the person is moving, etc.

- Use clay to create a sculpture showing MOVEMENT and action. Remember that curved and diagonal LINES and FORMS (three-dimensional) help create excitement and the illusion of MOVEMENT. The sculpture can be of a person or an animal running, jumping, climbing, etc. A sculpture of a tree blowing in the wind also shows movement.

- Create a painting or a drawing showing what you think happens next, based on what you see in one of the Remington scenes.

- Use blue, white and black crayons or chalk on blue paper to create a snowscape, with a high horizon line, similar to The Scout: Friends or Enemies?. Tear or cut an animal shape from colored paper (horse, deer, buffalo, bear, coyote or wolf) and glue this in the FOREGROUND. Remember that foreground objects are larger, more detailed and more saturated with color than objects in the background. Tear and glue small, irregular shapes across a short line near the HORIZON LINE to create an illusion of dwellings in the distance. Refer to the artwork as your example.

- (5th Grade) Examine the anatomical correctness of the horse pictured in The Scout: Friends or Enemies?. Use pencils or charcoal to sketch a horse.

- (Grade 3-5) “Become” the scout. What will the scout say when he returns to camp? Did he encounter Friends or Enemies? Write a story about the situation pictured.

- Create covered wagons with small boxes and white construction paper. Cut wheels from cardboard and attach to the box with paper fasteners. Small milk cartons, cut in half vertically, or shoeboxes will work too. Waxy milk cartons will need to be covered with brown paper. Paint shoeboxes. Use oxen pattern and attach teams with yarn.

- Paint a western Landscape the way it looked in Frederic Remington’s time—without fences, cars, buses, highways, factories, airports, or cities.

- Bring in a fancy pair of cowboy boots to display. Drape a contrasting, solid color piece of cloth over a small box (taller than the boots) behind the boots and across the table. This will create a nice single color background behind and underneath the boots. Older kids can sketch the boots (and color them if you have time) as a Sill Life. Cut a black or brown boot shape from construction paper for younger kids. Kids can use ornamental LINE and decorative SHAPE, cut from colored paper, to create a fancy cowboy boot.

- Draw a scene of Indian life in winter during the time of the late 1800’s in America. Draw one main character in the foreground of your scene. Use heavy crayon to color the scene. Use watercolor resist filling the background with color, blue in the upper part of the picture and appropriate color below. Sprinkle wet paint with salt for special effect. Brush off when dry.

- Indians communicated with a picture language. Find actual symbols or create shape symbols to show human form, a horse, moon, stars, water and mountains. Draw a picture story with the picture words and present it at the front of the class, explaining what each symbol stands for as you go along.

(Grades 4-5) Create a three-dimensional paper mâche or clay cowboy, Indian, or female pioneer sculpture.

American Western Art

Frederic Remington was an artist who painted and sculpted the American West.

Can anyone show me on the map which part of the United States that would be? That’s right; it is any land west of the Mississippi River. (Be sure you, or someone, point this area out on the map.) That’s a large area of land, isn’t it?

When Frederic Remington painted the pictures we are going to see today, most people who lived in the Eastern United States had never seen the Western United States and had no idea what it looked like. Most western areas in Remington’s time did not have paved roads. Nobody could just take quick snapshots of the American West and send it to the curious people in the east. The only way to see what the West looked like was to have someone travel there and draw it.

Because so many people wanted to see the “Wild West”, many magazines and newspaper companies sent artists to sketch pictures. These simple line drawings were printed in magazines and newspapers all over the east. Many magazine and book authors, who had never seen the west themselves, made up exciting fictional stories of western adventures, to go along with some of these drawings. It sold magazines and newspapers and made people believe that life was glamorous in America’s Wild West.

Would any of you have liked the job of a magazine artist, to travel and draw pictures, so that people could see what unknown places looked like?

What kinds of dangers might you have faced?

How would you have traveled West in the 1800’s?

Many artists who journeyed West would take their many western sketches back home to their studio and paint colored versions of the things they saw in their travels. There was no such thing as colored photography back in those days. Artists who could paint very realistic scenes of the west had plenty of people interested in buying their paintings.

Why do you think artists didn’t just sit down and paint a picture while they were looking at it? Wouldn’t it have made it easier to get the colors “just right”? Why did they wait until they got home to do their paintings?

The mountains in the West are twice as tall as mountains in the East. There were no broad, flat prairies or vast deserts in the east. The land itself looked very different.

What do you think people from the Eastern United States thought or felt when they saw these paintings for the first time?

Do you think the paintings made people want to travel west to live?

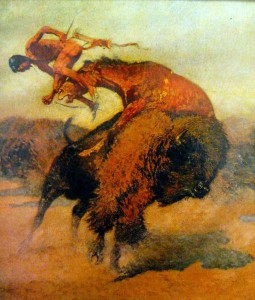

1. “The Episode of the Buffalo Hunt” (1895)

About the Subject

Although Remington and other people of his time referred to these animals as “Buffalo”, they are actually Bison. For the Indians, this plentiful range animal was a means of life. Food, clothing and tools came from the Bison. Tents, boats, bedding, ropes, saddlebags and bowstrings were made from its hide. Its horns became spoons. Colorful ceremonial masks for sacred dances were decorated with its horns and the Bison was used as a sign of distinction on brave Indian’s war bonnets.

By the 1820’s, Buffalo hunting for profit had begun in the United States. Yet, in 1850, herds still totaled 20,000,000 and often blocked the passage of railroad trains where they crossed the wide prairie. Amazingly, forty years later, these animals numbered only 551.

Suggested Dialogue

What type of MOOD has the artist painted? Frightening, dangerous, exciting

The painting is charged with dramatic and breathtaking excitement.

From which part of the landscape (foreground, middle ground, or background) is the action taking place? Action and danger burst from the center (middle ground) of the picture.

What “story” does this scene tell? A racing Bison, with his massive head lowered, has turned and reared, lifting the gasping horse completely off the ground. You cannot even see the horses back legs beneath the large head of the Buffalo. The rider has been tossed high into the dusty air. Taken by surprise, the Indian hunter holds his bow in one hand, while his arrow quiver strains from its leathered thongs behind him. It looks as if the Indian is in for a very dangerous, head first fall, because the dusty shapes around this scene seem to be a perilous buffalo stampede!

Hunting Buffalo was always dangerous, even more dangerous before Europeans introduced horses to America. When Indians began hunting Bison on horseback, it was still terribly hazardous, as we can see from this picture! Before horses, an Indian hunter had to approach an enormous Bison on foot, within a few feet, so that his first well-directed arrow would down the fierce animal. If the buffalo did not fall with the first arrow, the hunter’s life would be in great danger from the angered beast. Since Buffalo travel in large herds, the hunter had another reason to be careful. A large herd might trample the hunter if the huge animals were suddenly alarmed.

As an athlete himself, Frederic Remington understood and admired the courage of the strong Indian hunters and their well-trained horses.

How did the artist create MOVEMENT? The Indian is hurling through the air in the same position as when he was sitting on the back of the horse, just a second before; hurled through the air so fast that he hasn’t even had time to change position yet. CURVING SHAPES, as well as CURVED and DIAGONAL LINES help create a feeling of action and MOVEMENT. The horse’s odd position, (his front legs straddled over the back of the buffalo) has created a curving line along the back of the horse. (Move your finger along the horse’s spine, to his neck, as you point this out.) The front leg of the Bison is up in the air and the giant beast seems about to fall over. The artist has also painted dust around them, another indication of MOVEMENT.

What do you think is going to happen next?

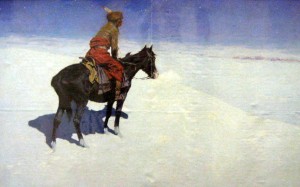

2. “The Scout: Friends or Enemies?”

Frederic Remington’s scenes of cowboys, Indians, hunters, trappers, and soldiers were printed in leading magazines of his day, including Harper’s Weekly, a popular magazine publication. Remington romanticized the American West and passed on the drama of the frontier and its characters to an America that, during Remington’s time, wanted to see themselves as heroic frontiersmen, braving life and death struggles against overwhelming forces. The “breathing space” and energy of the West fascinated Remington.

Suggested Dialogue

This painting presents a serious question. The Indian scout is unsure whether he faces friends or enemies as he stares at a cluster of dwellings near the HORIZON LINE. Will they be friendly or is it dangerous?

Describe the MOOD of this painting? Is it Lonely? Peaceful? Tense? Cold?

Is the scout being reckless or cautious? What does he see? Ask kids to trace an invisible line from the Indian’s eyes to the shadowy mass on the horizon. The scout seems to be watching, waiting, almost frozen in the snowy landscape.

Is anything moving? Look at the wind blowing the horse’s mane on the back of his neck. It also blows the Indian’s fringed tassels on his sleeve and the horse’s tail.

Can you see the horse’s wispy breath? (Have someone point this out to the class.)

Do you see mostly WARM or COOL COLORS? Cool

Who can list all of the COOL COLORS for me? Blue, green, violet

Which are the WARM COLORS? Red, yellow, orange

What is the most important COLOR in this Landscape—white or blue? Blue—Notice how Remington bathes the white with TINTS of blue, to freeze the ground and sky together. Look for the bright white hoof prints. You can also find blue on the horse and rider. Even the shadow is blue-black. (WHITE is the absence of COLOR.)

Point out the CONTRAST between the cold landscape and the earthy browns, blacks, and rusts that outline the figure. It is hard to find the HORIZON LINE because the various TINTS of blue blend and mix with the dark blue of the night sky. This could be blowing snow, a frozen river’s edge, or even hills. We can see small, roughly defined, contrasting colored shapes forming a line in the distance, on the right. Sparkling yellow sprinkles the sky with stars and suggests either fire or torches in the distance.

What type of BALANCE does this scene have? Each side of the picture is different. ASYMMETRICAL BALANCE helps create a feeling of distance. The darker blue sky and the huge expanse of blue white ground balance the strong color and size of the Indian and his horse.

Why are the horse and Indian so much larger and more colorful than the rest of the picture? These are closest to the viewer, in the FOREGROUND. Their COLOR is most intense. Things in the BACKGROUND have less intense COLOR. SHAPES are smaller in the background, larger in the foreground.

Discuss the theme of the painting—is this image typical of the stereotype of a fighting Indian? Do you think the others (implied in the background) should be afraid of this lone Comanche? Should he be afraid of them?

Discuss what occurred in America before this picture was painted—Custer’s Last Stand, 1876; capture of Geronimo, 1886. Ask kids to consider how these events may have influenced Remington’s choice of subject.

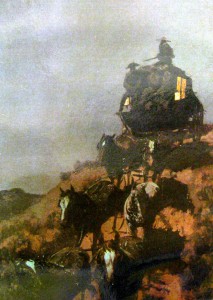

3. “The Old Stagecoach of the Plains” (1901)

Surprisingly, Remington’s night scenes are filled with light—moonlight, firelight, and candlelight. This painting of a stagecoach passing into the night helps us imagine the hazards of travel through Indian country during the 1800’s.

Who can describe what they see in this scene?

The scene is bathed in moonlight, creating shadows under the stagecoach and the horses that pull it. The sky is sprinkled with small white dots, creating stars.

This is one of Remington’s most dramatic nighttime scenes. Against a starry sky, the candlelit coach rushes through the night. A guard, with his protective rifle poised, sits on top of the coach, scanning the horizon for some unseen danger.

Art critics liked Remington’s night scene paintings. Yet, the artist himself felt that he could never quite accurately capture the colors of night. In 1905, Remington expressed his frustrations with color to a friend: “I’ve been trying to get color in my things and still I don’t get it. Why, why, why can’t I get it? The only reason I can find is that I’ve worked too long in black and white (referring to his line drawings done for magazines and newspapers). I know fine color when I see it but I just don’t get it and it’s maddening. I’m going to if I only live long enough.”

Can you find the HORIZON LINE in this picture? The implied horizontal line where the sky and the earth meet

Can you find where the artist used the technique of OVERLAP, to help create depth in this scene? The coach is coming down a hilly incline and we can see that this hill overlaps another one on the far left, making the hill on the right seem closer.

Where is the moon? The moon shines from above, on the left.

How do we know? We can’t see the moon, but we know where it is because of the shadows cast by the stagecoach and the horses, which fall to the right.

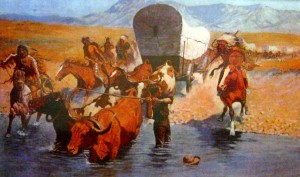

4. “The Emigrants” 30” x 45” (1904).

About the Subject

During the 19th century, several hundred thousand American settlers moved west. When pioneer emigrants first traveled across the plains, they came in covered wagons. All their belongings were loaded into these white-topped wagons, as well as food and water. Many wagons often grouped together for the westward journey and formed a wagon train. For protection at night, the wagons were circled and campfires were built inside this circle. Settlers slept both in and under their wagons, also in tents.

Oxen were the most popular animals to pull these wagons, preferred for their strength and durability. They were less expensive than horses and oxen and did not require the more expensive equipment that horses used. Oxen used simple wooden yokes instead of harnesses. People “drove” oxen by walking along the left side and used a whip or prod to urge and guide them along. Oxen were trained to respond to shouts of “gee” (right turn) and “haw” (left turn). Under normal conditions, oxen could pull a heavily loaded wagon at about two miles an hour.

Covered wagons had no shock absorbers, so the ride over bumpy trails was uncomfortable. Most kids, unless they were very small, walked the majority of the time. Nervous parents tried to keep small children inside the wagons, but they would often become restless or curious and move in and out of the wagon as it rolled along. The heavy dust from the wagons made kids choke and cough as they traveled along the dry trails.

The trip was filled with danger. There were Indians, wolves, poisonous snakes, accidents, starvation, and exposure. Indians frequently worried the travelers and there were some tragic encounters, but Hollywood has mistakenly made it seem as if Indians had little more to do than attack wagon trains. The plains were hundreds of miles long and wide. A number of pioneers saw only small groups of Indians along the way. Some Indians even assisted these early travelers. The danger of Indians was small compared to the very worst dangers of the long journey—sickness and accidents.

Sickness was the worst threat to the emigrants than all other dangers combined. Common lethal diseases among travelers included scarlet fever, smallpox, and typhus, all spread through personal contact. Poor sanitary conditions caused dangerous intestinal diseases like cholera and dysentery.

Accidents were the second worst peril on the trail. Falling beneath the wheels of a heavy moving wagon seriously injured or killed more children than any other type of accident because there were no hospitals along the way to take care of injured people.

In the 1800’s, teenagers were viewed as grown-ups and carried full adult responsibilities, such as driving the oxen of a covered wagon. Some teenage boys even earned their own way West by driving an oxen team.

This scene painted here tells an actual true story, recounted to Remington by a man (depicted as the boy in the water) who was attacked by Native Americans, when driving a team of oxen on his way west. The boy was scalped, and left for dead, but he survived and grew up to share his adventure with the artist. Remington admired the man’s courage so much that he painted a picture of his story, although he left it up to our imaginations to decide what happened next.

Suggested Dialogue

Remington’s artwork often created dramatic or dangerous adventure. Many of his scenes of frontier settlers’ contact with Indians portray conflict. In real life, whenever Indians chose to attack a wagon train, it was when the wagon train was in a vulnerable position, such as passing through a narrow gorge or crossing a river, as in this painting. Most of the time, Indians stayed away from wagon trains.

What features are seen in the Foreground? Two oxen have just entered the river to pull the wagon across. Armed Indians on horseback are racing up on either side, towards the teenage boy driving the oxen. The only emigrant visible is the boy, defending himself with the pole used to drive the oxen. He has lost his hat in the river.

(Grades 3-5) Describe three ways the artist created DEPTH in this Landscape. Size-the oxen and wagon in front are much larger than those behind. Position-the wagons behind are higher on the picture plane. Detail-wagons behind have much less detail than the one in front. Color-objects in distance have lighter color than foreground.

(Grades 3-5) Identify the type of BALANCE used in the Landscape. Asymmetrical—if the picture is divided in half, it is different on each side.

(Important Question for Grades 3-5) How did the artist create BALANCE using LINES, SHAPES, and COLORS?

The largest SHAPE in the picture, the MIDDLE GROUND wagon, divides the scene almost in half, creating ASSYMMETRICAL BALANCE. The SHAPE of the boy also divides the scene. (Follow the implied vertical LINE of the boy’s body, up towards the opening of the wagon covering.) Most of the wagon SHAPE is on the right, giving the right side, which has mostly small SHAPES, more visual weight. The SHAPES of the Indians, horses and oxen on the left are larger, more numerous, and have more intense COLOR than the shapes of the Indian, and LINE of distant wagons on the right. The right side has lighter COLOR because these objects are farther away. The visual weight of the larger, darker, and heavier wagon SHAPE balances the scene by making each side more equal.

5. “The Apache”

Whenever he painted or drew Native Americans, Frederick Remington always clearly distinguished the difference between a Sioux Indian or an Apache. Each Native American tribe had their own distinguishing styles in the details of their dress, jewelry, or hair. Sometimes blankets, baskets, leather pouches, knives, spears, or other accessories had identifying design styles or techniques that helped distinguish a warrior’s tribe. Remington was very careful to correctly paint the details, and to do it so realistically, that any Apache Indian of his time would have easily recognized the Indian in this painting as an Apache, not a Sioux!

This painting stirs our imaginations. A story is about to unfold here. What is about to happen?

What kind of MOOD does the painting create? A feeling of imminent danger

The scene reminds us of the stories of the old west that have been created in books and in movies—an Indian is about to attack a wagon, illustrating the familiar cowboy and Indian conflicts of Hollywood’s Old West.

How many of the 5 basic LINE TYPES can you find in this painting? The Five Basic Line types are: horizontal, vertical, diagonal, curved and zig zag—this is a good time to review what these are.

Where do you see HORIZONTAL LINE?

Can you find VERTICAL LINE in the scene?

Do you see any DIAGONAL LINE? The trail the wagon is traveling on, the ground beneath the horse’s feet, spiked limbs and leaves of the foreground plants, far right edge of HORIZON LINE

CURVED LINE? Bridle reins over the Indians arm and under the horse’s neck

ZIG ZAG LINE?

(Important Question for Grades 3-5) How did the artist use SPACE in this Landscape?

POSTIVE SPACE—The Foreground rocks, the Indian, his horse and rifle, the foreground plants, the covered wagon and horses in the distance.

NEGATIVE SPACE—The grasslands of the middle ground and foreground, the sky and hills in the distance.

(Important Question for Grades 3-5) Explain three ways the artist created DEPTH in this Landscape.

SIZE—The horse in the foreground is much larger than the wagon and horses in the middle ground, which makes the covered wagon seem farther away.

OVERLAP—One spiked limb of a foreground plant overlaps the wagon, making plant appear closer.

DETAIL—The horse and Indian have more detail than the wagon creating distance.

COLOR—foreground objects, Indian and horse, have more intense color than background wagon and horses.

POSITION (placement)—objects lower on the picture plane (bottom) appear closer (foreground), middle ground is a little higher and just a little farther away, background is the highest area of the picture.

(Important Question for Grades 3-5) What feature(s) did the artist put in the FOREGROUND of this landscape? Indian, horse, large rock, plants

(Important Question for Grades 3-5) What feature(s) did the artist put in the MIDDLE GROUND of this landscape? Wagon pulled by horses, wagon trail

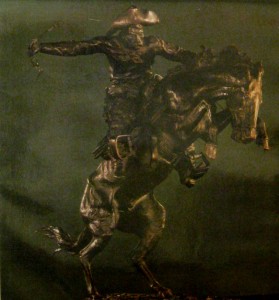

6. “Bronco Buster” (1895)

About the Artist

Frederic Remington’s love of horses dated from his childhood years. His drawings and his skill as a rider won him friends in the west, where a cowboy often had six to eight horses. Remington requested that his tombstone epitaph read: “He knew the Horse.”

Remington admired cowboys and said that cowboys, “Possess a quality of sturdy, sterling manhood, which would be to the credit of men in any walk of life.”

About the Art

Frederic Remington had no formal training as a sculptor and probably invented his own creative sculpting techniques. Ricardo Bertelli, of the Roman Bronze Works, was a skilled craftsman whose care assured high quality in Remington’s bronze sculpture. The two men were good friends and often worked together in the foundry, casting many of the artist’s fine sculptures.

Remington decided to take up sculpture because, as he wrote, “My oils (referring to his paintings)…will look like pale molasses in time—my watercolors will fade—but I am to endure in bronze…”

What do you think the artist meant by this statement? A cast Bronze sculpture is very sturdy and would last hundreds of years. Ancient bronze artifacts exist today.

The bronze for this sculpture was cast on Remington’s 34th birthday—October 1, 1895. This was Remington’s very first bronze cast sculpture and many more castings were made of this piece than of any of his other sculptural works.

Suggested Dialogue

(Display the poster with examples of Classic Sculpture types)

What classic type of sculpture is Remington’s Bronze sculpture? Full round, the image is created on all sides and is freestanding

What is happening in this sculpture? A cowboy is riding a horse that is rearing up on its hind legs. The horse does not seem to have a bridle or a bit, just a long rope tied at his jaw. The cowboy is training the horse to be ridden with a saddle.

Is the horse happy with what is going on? How do you know? Because the horse is rearing, we can tell he is trying to get rid of the rider. The horse is not happy about the cowboy on his back, who also has a whip in his hand.

What type of MOOD (feeling) does this sculpture create? Excitement, suspense, challenge, danger, action

How did the artist create a feeling of MOVEMENT? Curved LINE, SHAPE, FORM help create a sense of MOVEMENT. The horse stands on only two legs, his head is curved and his front legs are curved, as if frozen in a moment of movement. The pose of the cowboy’s arm in the air, with the curve of his whip, also creates action.

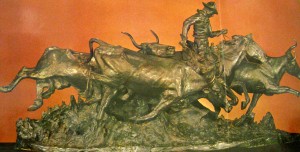

7. “The Stampede” (1909)

About the Artist

Remington’s art made him famous by the age of thirty. In his twenty-three years as an artist, Remington wrote 8 books, created 2,739 drawings and paintings, and 25 bronze sculptures. Frederic Remington died at the unexpected and early age of only 48, on December 26, 1909, because of a ruptured appendix.

President Theodore Roosevelt, who greatly admired Frederic Remington, wrote this about the artist in 1910:

“The Indian is civilized, the cowboy is passing, the range cattle are taming, even the Cayuse (Indian Pony) is passing into history. One man’s work, however, will preserve them for all time in pictures and in bronze…This man was Remington.”

About the Art

This sculpture was the last created by Frederic Remington and it was completed shortly before his death.

Is this a quiet and “still” type of sculpture? No, just like Remington’s other sculpture, Bronco Buster, the artist has created a feeling of intense MOVEMENT and action. Point out the way that even the background shadow, created by the sculpture, intensifies this sense of movement and helps create the feeling the title suggests—Stampede.

What ways has the artist created a sense of MOVEMENT in this sculpture?

What type of TEXTURE can you see?

Is this a two-dimensional creation or a three-dimensional one? Sculpture is three-dimensional; meaning it has height, width, and depth (or thickness). Paintings or drawings are two-dimensional; they have height, width, but no measurable thickness (or depth).

Frederic Remington’s sculpture is FULL ROUND, meaning that you can walk all the way around it and see that it as realistically sculpted in the back as it is in the front.

To create a sculpture like this, the artist first uses wax, like clay, to sculpt a FORM. The wax sculpture is set up with a hollow tubing system and dipped into a ceramic mixture, dried, and then fired at a high temperature, to make the ceramic hard. The sculptured wax melts inside the ceramic shell and the wax flows out the tubing system, leaving a hollow mold. In the next step, melted metal (bronze) fills this ceramic mold and is allowed to cool. Once the metal cools, the ceramic mold and the tubing are broken off and a “cast” metal sculpture, which looks just like the original wax sculpture, is revealed. The metal is then filed and smoothed to become a beautiful and lasting metal sculpture.